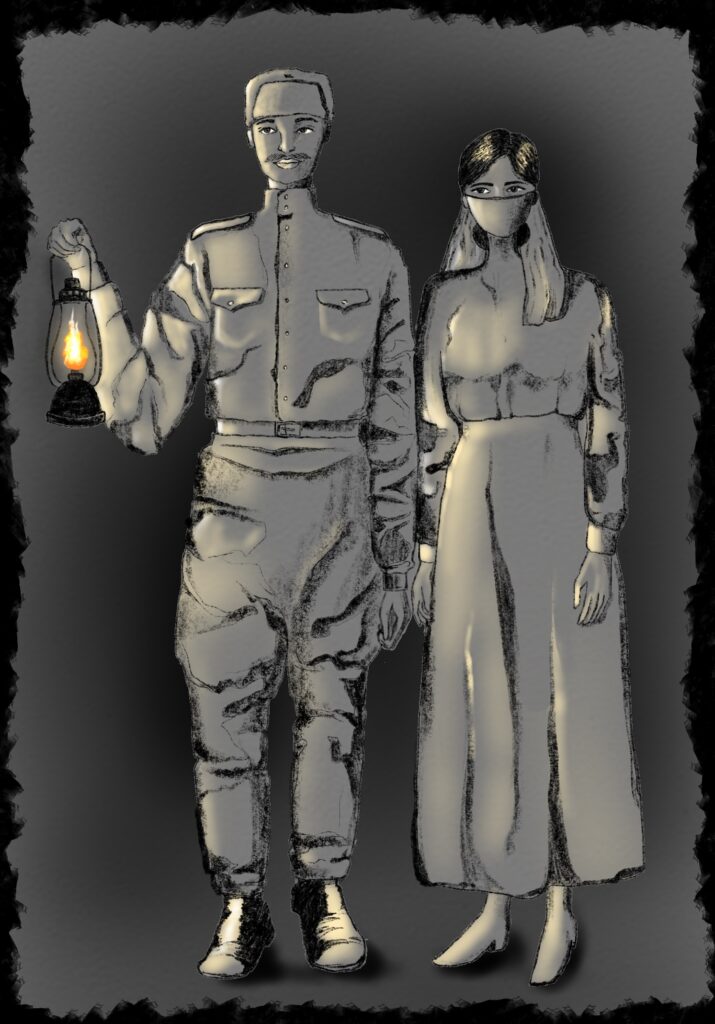

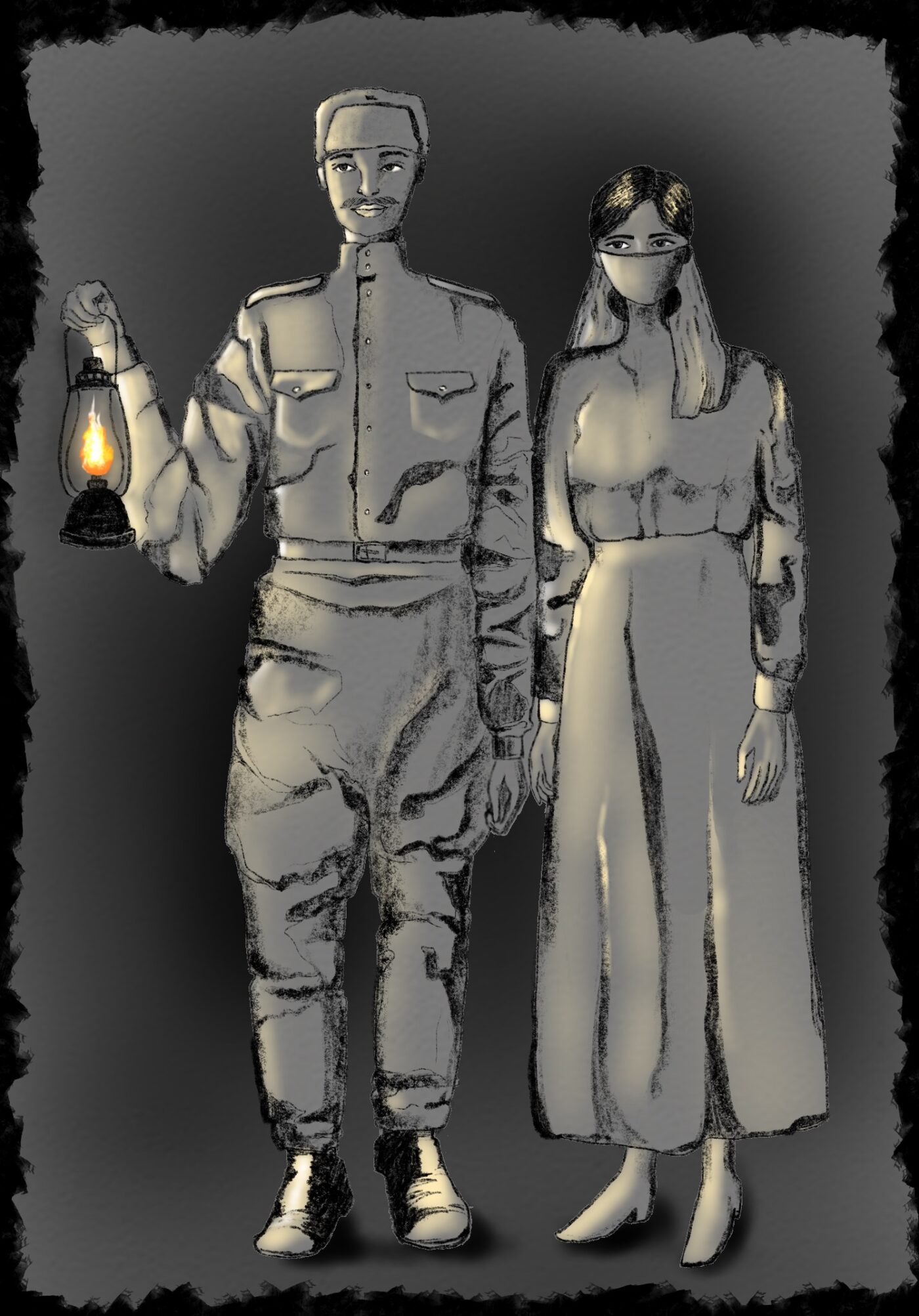

WILLIAM

I wake up with a dull, numbing pain in my temple. My arms are still sore from carrying the only bag I own up to the 12th floor of my apartment building. I slowly get out of my rickety bed and head to the washroom to freshen up and start my day. I look into the mirror—tired, light brown eyes stare back at me, the eyes of a prisoner of war with no one to come home to.

After a cold shower and change of clothes, I head downstairs to get a copy of the newspaper.

“Spanish flu claims another 523 in the Capital.”

“Can Britain win the war against the flu as well?”

These headlines, written in big and bold Hobo font, catch my eye. They were messages of doom that had been circulating for a few weeks now. The Spanish flu was killing people mercilessly; especially soldiers cooped up in the trenches who waited to go home or be given a quick and painless death. As I scan the pages, my mind wanders back to the dreadful war years.

In 1916, roughly two years ago, I wished for the latter at the Somme Offensive. But life has a funny way of never giving you what you want. A million people died at the Somme, enemies and allies alike. Yet, my wish was unfulfilled, and I survived to live in suffering.

In the last waves of the Offensive, I had rushed low and quick towards the enemy trenches only to get shot in my thighs and fall right into the enemy lines. It reeked of alcohol, sweat, urine, and fear— a vile combination all too familiar during the battle days. I tumbled right in front of a medic and looked into his sunken eyes as I thought, “Will he kill me? Or will he leave me here to bleed out?”

I wished for death because suffering in this cruel world was not worth my bravery. So I stayed there unmoving for what seemed like an eternity until the medic did something I never expected. He picked me up and carried me inside an empty bunker whose walls were splattered with black soot from grenade attacks.

He rested me against the wall and gently dabbed my wound with alcohol. I flinched in pain as he explained something in rapid German and then shoved a wad of dirty cloth into my mouth. He mechanically wrapped the area above the wound and cut off the blood supply. That’s when the hell began—he took a pair of heated tongs and removed the 7.62mm as the blood slowly oozed out. I writhed in excruciating pain as my head soon felt lighter and my vision darkened.

The thoughts of those horrid days flit in my head like flies in the summertime.

I quickly have my breakfast and head to the veteran’s rehabilitation centre to get my injuries checked. The street I’m walking on barely has any traffic on it since the Government placed restrictions on transportation and public gathering. The apparent “flu” outbreak was written in the papers as utterly natural like it was just the flu season. But soon, it started taking lives in triple digits. Either people developed immunity, or they died.

It is as simple as that.

I reach the centre and head inside to the reception. A nurse leads me to a room further down a maze of corridors and stairs.

“The doctor will be with you shortly. Please wait inside.”

The morning sun rays illuminate the room I walk into. I notice a cabinet on the wall with a medal of honour inside. It’s from the war. Those medical officers that survived the war and the sudden flu were made to work in the rehabilitation centres to help the veterans in both psychological and physiological manners.

I was here for both.

“Ah! Sorry to keep you waiting. I had to check up on one of the flu patients. This one won’t make it to the next dawn,” he points. “That’s another one to the pile of bodies.”

I look at him expressionlessly and slowly say, “You still don’t believe what I saw and heard, do you? You still think this is a normal flu, don’t you?”

“You can’t expect me to believe what you say without any proof. And even if I did, what can I do about it? I’m just a doctor. I’m just a person who’s tried to give my patients an easier death. I served in the war, after all. Whoever saved you probably tried to give you a less agonising death, too, didn’t he?”

I remain silent. Deep inside, both of us know we’re right.

“Now then, let’s see the wounds on your back. Take off your shirt.” He finally says.

After examining them, the doctor gently looks at the scars on my face and says, “Well, everything is healing as it should. You should be completely healed by the end of this week. Try not to move out of your house too much. It would seem unfit for a former prisoner of war to die from influenza, of all things.”

As I exit the room, I realise no one will believe my story. My friends already think that I am mentally shaken from my time in prison. I don’t blame them, though. The last time they saw me was two years ago in Somme when everyone was unsure of their future. Somme was a disastrous masterpiece painted by the fallacies of the British Commanders and Generals.

A tap on my shoulder snaps me out of my thoughts. I turn around, and it’s the nurse who escorted me to the doctor’s office.

EMILY

The air reeks of death as I step outside the three-storey brick building I live in. I feel my mask and find it securely in place. The folded gauze was held together with tape. It used to give me a sense of safety, but that was until I had a niggling suspicion that it couldn’t stop the Killer.

Killer. That’s how I think of the disease in my head now.

I reach a shabby house with an unkempt lawn three blocks down the street. I knock on the door and wait for several minutes before the baker—an older man with kind, tired eyes opens it. He’s wearing a mask made out of cheesecloth. The inside is cold and cluttered, and in the corner of the living room lies a single dilapidated cot. The man’s daughter is on it, coughing heavily. I make my way towards her and begin by checking her temperature. She’s running a fever and shows signs of pneumonia. She’s young— in her late twenties, not much older than me.

It never gets easier to look someone in the eye and say their loved one won’t make it, but I do it anyway. His eyes lose the little remaining light. I could stay and comfort him, but there are many more houses I need to visit because some people couldn’t find a bed at the hospital. I leave, muttering a prayer.

The lanes are strewn with gauze. I hold back a scream. People were dying by the score every day in my locality. Still, no one wanted to see it as anything other than common flu. It didn’t make sense. The flu doesn’t kill people in their prime, yet the patients who died the most were between twenty to forty years of age. My colleagues shut me down every time I brought up my suspicions—maybe they are just scared. We are running short of medical supplies and staff; the war had claimed both. I shut my eyes tight for a moment and try to breathe. “Be strong,” I remind myself.

Some hours later, I walk into the rehab centre and quickly change into a fresh uniform. I dispose of the gauze carefully and wear another one. I step out to find a man by the receptionist’s desk who has an appointment with Dr. Hill. So I lead him to the consultation room.

“The doctor will be with you shortly. Please wait inside.”

I’m ready to walk away, but the conversation between the doctor and the man stops me in my tracks. He didn’t think it was a regular flu. My heart races as I wait for the doctor to finish. I retrieve the man’s file as he leaves the room, disgruntled. My hands shake uncontrollably as I read its contents. He was in the Somme Offensive.

I sprint across the winding hallways and reach him just as he steps out of the premises.

WILLIAM

“Excuse me, Sir. I need to ask you some questions.”

It was the nurse from the reception.

Thinking it might be another form to fill out, I ask, “Questions? I’ve already filled out the formalities, right?”

“No, sir, this has nothing to do with the centre. I overheard your conversation with Dr. Hill.” She takes a deep breath and continues, “Why do you think this is not some ordinary flu?”

“You won’t believe me anyway. It’s futile for me to talk about it.”

I turn to leave, but she stops me again. “Sir, please wait. I think this goes much deeper; it’s nothing like we’ve seen or heard before… except the Killer… No. Nevermind. I shouldn’t bring that up. I barely know you.”

With furrowed eyebrows, I question her, “Killer? What exactly are you referring to here? And you have heard about this disease before? You can trust me,” I assure her. This is the first time I’m hearing someone refer to the flu as a physical entity.

She furtively glances around and says, “The flu targets healthy people, young people forming the majority of the workforce. It feels intentional. It’s not only killing people… it’s killing everything one would need to survive. It’s not a normal disease—it’s the Killer.”

Her voice drops to a whisper, “And my sister… She was a military nurse at Somme when she died. Her friend who died shortly after that wrote to me. She had an unknown respiratory illness. The few symptoms like cyanosis that were mentioned in the letter are eerily similar to the Killer. You were at the Somme… surely you know something that I don’t?”

An overwhelming sense of urgency takes over me, and I reply, “What time does your shift get over?”

“It just started. I’ll be done by evening.”

“I’ll be back in the evening. I’ll tell you what I know then.”

The nurse hesitates for a second before saying, “Okay.”

EMILY

When my shift’s over, I rush through the door to find the man standing there.

“I’m here. Now what?”

He begins to walk without waiting to see if I’d follow.

I catch up in short, quick strides, and he eventually slows down his pace to match with mine.

“I was at the Somme two years ago, that is true, but what is it that you want to know?”

“Everything. Everything that makes you think the Killer isn’t ordinary.”

“The “Killer,” as you say it, isn’t a natural phenomenon, I am sure of that. People at the Somme died every day. It was the bloodiest battle in the whole war, with more than 16 million casualties.

His face turns ashen, and a part of me regrets bringing this up. But if he knows something about the Killer, it could save lives.

He sighs deeply before continuing, “Many died of exhaustion or were killed by the artillery, but people also fell prey to a rapidly spreading sickness. Except it didn’t seem that important. Maybe that’s natural when you know that tonight you might be blown up into pieces, or tomorrow you’ll be staring down the barrel of an MP-18.”

He briefly glances in my direction before continuing.

“A German medic saved me and took me to an unknown camp. In a war, it is not uncommon for countries to take prisoners, but I was neither a diplomatic bargaining chip nor was I an exceptional scientist who could be forced to work for them.”

A shudder passes through me, and I pull my tunic closer as the air turns chilly.

“At the camp, there were hundreds, probably thousands, who were either physically injured or mentally insane, or like me, just soldiers who didn’t get their wish to die. We were lab rats. The experiments done on me were mostly physical and did not last long. It was excruciating, but I wasn’t a part of the influenza experiments. That’s where things took a bad turn.”

I stare at him in horror, unsure of what to expect.

“Weeks after I got there, the scientists realised that the virus, which resulted in a sizable portion of the Somme casualties, was not contained. The whole camp had to be quarantined.”

No one would suspect them of sending infected troops. The returning soldiers unknowingly killed even more people. As a neutral country, Spain is the only one reporting the disease, but everyone thinks it just began to spread early this year. It was a clever plan. The virus is a weapon of war against humanity.

“But there was an explosion. It buried the camp in debris. Few survived, and the scars I bear are from that day.”

“You didn’t tell anyone about it?”

He chuckles sadly, “No one would believe me. I did not have evidence, and for them, I was a prisoner of war gone mad.” He adds, “But it did not stop me from gathering intel. I was afraid that if the original strain had survived, it would have killed people almost instantaneously. But I could not get very far. And the only thing I last heard were rumours of an even more powerful strain.”

“It doesn’t seem like it could have survived the explosion. You barely made it out alive.”

“I hope so. It’s getting late, and I need to go home. Is the centre open at this hour? I left my file there.”

“It’s open all day, but nobody goes there after sundown.”

WILLIAM

We make our way back to the centre to retrieve my file and find Dr. Hill treating a patient in the room opposite his office. He is holding a syringe with an amber solution—which looks similar to those used in the experiments.

But before he could inject the patient, he catches our eyes and stops.

“Dr. Hill, I’m glad our medical supply has been restocked. They said it would take at least three weeks.”

The doctor lets out a nervous laugh. “Oh yes. Emily! Hi, I’m… uh… glad that the centre is better equipped now. What are you doing here? Isn’t your shift over?”

“Oh yes, doctor, it is over. I had just been talking with this man about some things, and he just remembered that he left his file here.”

If my past has taught me anything, it’s to trust your instincts no matter what. During their conversation, I could only think of one thing. Dr. Hill was not here to save anyone. The serum he was using had the same colour, and the syringe’s barrel held the same markings as the ones in Germany. The pieces of the puzzle fall into place. The man in front of me is responsible for the death of my brothers-in-arms and millions of others. Dr. Hill is a double agent.

My body moves as if it has a mind of its own. In that moment of impulse, I lunge at his midsection, tackling him to the ground. His hand is still holding onto the syringe, and I realise I need to get it away from him before he can jab me with it.

Emily quickly swings in and pries his hand open, and takes the syringe away.

“What now?”

“Get me something to immobilise him. Then I’m going to make a call to my former Commanding Officer. I heard the old man survived through it all. He’ll know what to do with this bastard.”

Emily quickly follows my words as I keep him there pinned, with one hand tightening his throat every time he moves.

After explaining everything on call, Dr. Hill is taken away by uniformed men to the nearest military base to await further procedures. Desertion will lead to a high degree of punishment, but treason will be a direct order of execution.

I see Emily before leaving.

“Perhaps, you survived the Offensive because you had a bigger purpose,” she says. “You were destined to save people from this strain.”

I smile, knowing that tonight, my tired eyes will rest easier than they ever have.

EMILY

The following day I stood at the doorway of my house. Procuring the strain has proven to be quite valuable. A vaccine is being developed—we could see the light at the end of the tunnel. Dr. Hill was incarcerated, and it was a small victory I would celebrate one day. But until then, we had a battle to fight. I tape my gauze mask and go about my rounds.

Written by Aditya Kapur and Deepthi Priyanka C for MTTN

Edited by Aishwarya Sabarinath, Avaneesh M and Kaavya Azad for MTTN

Featured Image by Bhargabi Mukherjee for MTTN

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.