The wind blew cold, pricking and biting at his skin as it brushed past his cheek. The trails of his trenchcoat flew as if trying to run away.

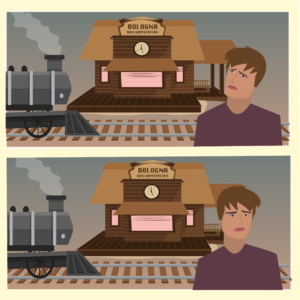

The tracks creaked under the weight of the trains. It was a normal Monday morning- as normal as any other day could be. People rushed past, children holding their parents’ hands and all those corporate workers screaming into their phones. The smell of coffee and bread filled the air- what else would you expect here? “Excuse me” someone pushed past him.

Where was this train?

He had been waiting for half an hour- he had places to be, why was the train late?

He looked around for the schedule board and his eyes landed on the infamous clock. The Bologna Railway Station clock. It ticked away, counting down the endless stream of time, uncaring as the hours passed away.

Had it not stopped working though?

He could have sworn it did.

He was very young when the blast of 1980 happened, maybe three years old, but he could have sworn that the clock had stopped after that. Everyone knew that. It’s what he had heard for years on end.

Someone brushed past him once again, pushing their way through the crowd to get to the train that had just come to a halt in front of him. Finally, train J-11. It had arrived. He gave into the flow of the crowd and rushed over to get on. Seats were always so hard to get and he was in no mood to stand.

Outside, the clock struck 1.

The case of the shared delusion of the stopped clock at the Bologna railway station is one of the many examples of the Mandela effect.

‘Mandela Effect’ – as coined by a paranormal researcher, Fiona Broome – reached the ears of social media in 2015, when famous YouTubers Shane Dawson and Jenna Marbles talked about it as a conspiracy theory on their respective Youtube channels and podcasts. Named after Nelson Mandela, this theory is remembering the details of an event that never happened in reality. In other words, the Mandela Effect is when a large group of people have a similar memory of an event or a fact which is completely false.

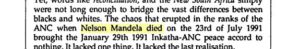

In 2009, Fiona Broome launched a website, reporting incidents that fit accurately into the description of this phenomenon. She claimed that Nelson Mandela, former President of South Africa, had died in the middle of his duration of imprisonment during the 1980s. Supporting this, a large number of people remembered witnessing a live coverage of his funeral in numerous television channels worldwide. Except, Nelson Mandela was freed in the 1990s and died in 2013. It didn’t help that African High School books published his date of death years before he was released from jail. A South African literature book called ‘English Alive 1990’ – published on October 1, 1991 – stated that Nelson Mandela had died on July 23, 1991.

It has been a part of a huge internet debate whether it was just the confusion of his imprisonment, an example of a psychological phenomenon of ‘false memory’, or an event that had occurred in an alternative timeline. Slowly, lots of similar examples of the Mandela Effect began emerging online that caused people to term it as one of the most famous conspiracy theories out there.

These examples are taken from the most common parts of our lives that we barely even remember. The game Monopoly’s mascot ‘Monopoly Man’ is pictured by everyone as a stout old man with a suit, top hat and monocles in their memories. He never had monocles. The famous cartoon show ‘Looney Toons’, which was a major part of all our childhood, was spelt ‘Looney Tunes’. The Queen in Snow White used to chant, “Magic mirror on the wall” rather than “Mirror, Mirror on the wall” as we all remember it to be.

And of course, one of the most influential and iconic lines in pop culture, “Luke, I am your father” is in fact never said in the Star Wars movies. The actual line said by Darth Vader, however, is “No, I am your father.”

There are hundreds of examples where people have mistaken or misremembered a certain detail of an event from their memory.

Soon, many psychologists and scientists began to step in to clear people’s confusion as the Mandela Effect hit the mainstream media.

So why does this effect occur? How can large groups of people all over the world have the same collective memory?

A very likely explanation for the Mandela effect can be false memories. Confabulation or false memory is the recollection of something that never happened. It can range from remembering the wrong date to something as large as fabricating memories of entire events that never took place.

Deese-Roediger McDermott Paradigm

An easier way to understand why false memories are present is through the Deese-Roediger and McDermott paradigm. The procedure, pioneered by James Deese in 1959, is a method in cognitive psychology to study false memories. This method demonstrates how learning closely related words such as ‘bed’, ‘pillow’, ‘blankets’, produces false recognition of related but non-presented words such as sleep.

Post-event Information

Another concept that could result in false memories is post-event information. The information you receive after the happening of a particular event can alter your memories of the same event. It is the reason why even eye-witness accounts can be unreliable.

Independent reports that one of the reasons people fall easily in the hands of these theories is the incorrect memory recall. It is associated with ‘schema-driven errors‘. The location of a memory in the brain is called ‘engram’ or memory trace. A schema is a cognitive pattern which organizes information in the brain into a particular structure or framework. Here, similar memories are arranged in closer proximity to each other. Research shows that people tend to use schematic processing to recall a certain memory of an event. An inconsistent pattern of action cannot be as easily remembered as a consistent one. For example, a person performing a simple, stereotypical task would be much easier to witness and remember than them performing a complicated one. In a doctor’s chamber, a stethoscope or a writing pad would be convenient to remember for a person than an unfamiliar object like a flower pot.

Hence, as the memory of the particular event fades with time, the chances of people misremembering its non-stereotypical details increases. Thus, there is an error in the memory recall of the person.

If people do not remember the unfamiliar details of an event, it is easy to doubt the credibility of these details. Mandela Effect examples are often attributed to such memory errors that occur in the human mind.

But the real question is, how do so many people share the very same false memory?

Many devices such as the internet can be put under the spotlight here, but this phenomenon has occurred since even before its invention. Perhaps someday more research into its origins will shed some light on this phenomenon, till then it remains to be a hotly debated topic amongst conspiracy theorists and scientists alike.

Written by Tanya Jain and Anushka Shrivastava for MTTN

Artwork and featured image by Sara Dharmik for MTTN

Edited by Shuba Murthy for MTTN

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.