Humans are predisposed to challenging an action they disagree with. Holding a person accountable for their actions is an act whose existence can be traced back to the early days of civilisation. “Cancel culture,” as it is known, is a derivative of that— rooted in modern society, and usually online.

What is cancel culture?

Cancel culture refers to the withdrawal of support for (cancelling) public figures or companies after they have said or done something considered objectionable or offensive.

It involves calling out the bad behaviour of public figures, boycotting their work (not watching their movies or listening to their music), and culturally blocking them from having a prominent open platform or career.

For how long has it been around?

The first reference to cancelling someone comes from the 1991 film New Jack City, in which Wesley Snipes plays a gangster named Nino Brown. In one scene, after his girlfriend breaks down because of all the violence he’s causing, he dumps her and suggests to cancel her.

The trend of calling someone out worked as the groundwork for a more comprehensive boycott, and eventually gave birth to cancel culture. The practice has its roots in the early-2010s. Tumblr blogs, notably “Your Fave Is Problematic”, where fandoms would discuss why their favourite stars were imperfect. Louis Tomlinson’s entry in Your Fave Is Problematic: Louis Tomlinson used “You act like a little girl” as an insult, and made a misogynistic joke directed at his then-girlfriend.

Although the term has only grown in popularity on Twitter in late 2017, the term “cancelling” was initially used in 2014, in a completely different sense— with regards to the non-renewal(cancellation) of a TV show.

How does it affect us today?

Since its rise in usage, it has more often than not been seen from a negative standpoint. People claim that its toxic nature—with everyone targeting and “attacking” someone at any given opportunity—infringes upon their right to free speech.

The act of digging up years-old messages and taking them out of context to expose someone has worried people. People can’t freely express what they think and feel, and if they do so, they have to be word-perfect and extra conscious. It makes them feel like they cannot learn from their mistakes because they aren’t allowed to make any, for fear of having to live with the outfall publicly and forever.

The fact that being online and behind a screen makes it so easy to dehumanise and call someone out—not gently— just adds onto the many reasons cancel culture has gained traction. Although at times, it has been a useful tool for bringing forth problematic people and having them repent for their actions.

The impact it has had

Cancel culture developed hand in hand with the #MeToo movement following the exposure of the widespread sexual-abuse allegations against Harvey Weinstein in early October 2017. He was convicted for rape and other sex crimes, while financier Jeffrey Epstein died while awaiting trial for sex trafficking in 2019 – but many are still facing their biggest recriminations online.

So, what’s the truth? Is it a myth? Does it only exist when its use is a convenient method for someone to justify their behaviour online? Do guilty people use its supposed brashness to gain sympathy?

Well, the fact is, it’s rather situational—it has been observed that if the cancelled individual is a celebrity making a controversial but-not-too-outrageous statement, it’s safe to say that they usually get off the hook. Seeing as they have a massive following, it is guaranteed that at least a small percentage of followers would back the celebrity up; as a result, their lives are unaffected, their career is still stable.

It’s the same when it comes to topics wedged deep in political discourse— there’s always enough supporters on one side for someone to stay afloat. Although it’s not all bad— many individuals have been held accountable because the public rose to the occasion and cancelled them.

Let’s take the case of Kevin Spacey. On October 29, 2017, actor Anthony Rapp alleged that Spacey, while appearing intoxicated, made a sexual advance toward him in 1986, when Rapp was fourteen and Spacey was twenty-six. Fifteen others then came forward alleging similar abuse.

As a result of the allegations, filming of the final season of his hit TV show, House of Cards, was suspended. The season was then shortened; he was removed from the cast and as executive producer. Gore Vidal’s biopic Gore starring Spacey, was cancelled and Netflix went on to sever all ties with him. He was also replaced in the film “All The Money In The World”.

The criminal charges brought against him have now been dropped, and he denies all allegations. Nevertheless, his cancellation seems to have effectively ended his career.

People have even cancelled others by exposing them to gain wealth and popularity through sympathy or other such means— by stepping on them, figuratively speaking.

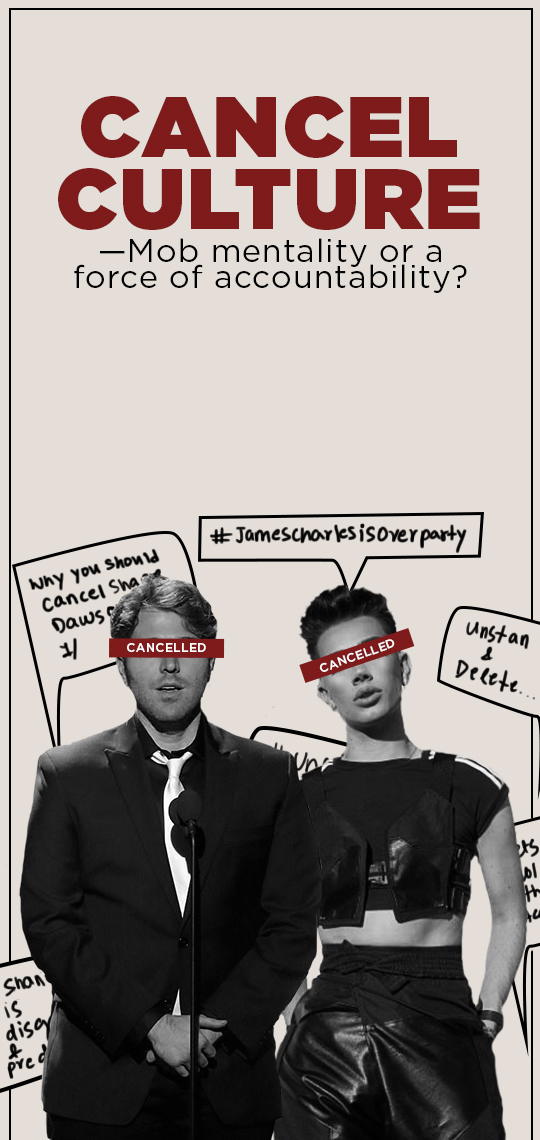

James Charles, one of YouTube’s biggest beauty and makeup stars, was accused of racism, transphobia, predatory behaviour and ripping off his fans. His feud with Tati Westbrook—his mentor and an influential member of the beauty community—took off on May 10 with Westbrook’s “Bye Sister” video and went on for 9 days until Charles declared a truce on his Twitter account.

The drama initially cost Charles about 3 million subscribers— he ultimately gained back about 2 million— while Westbrook gained nearly 4 million subscribers from the exchange.

On May 18, 2019, Charles made a second, forty-one minute, video addressing the comments made by Westbrook, entitled “No More Lies“. It presented evidence appearing to refute many of Westbrook’s accusations and led to renewed support for Charles and criticism towards Westbrook.

It’s harder for influencers to recover from a “scandal”; their product is their platform. Their biggest asset is the attention they attract on social media, so being cancelled cancels their worth. It cuts their power as an influencer and their value to marketers, and they lose the trust and support of their followers.

Cancel culture, in some cases, may provide a platform for spreading hate by spinning stories out of control, spreading misinformation and slander resulting in innocent people getting hurt. A case where all the facts aren’t present and a person is ill-informed acts as a spark that can spread like wildfire, wreaking havoc and outrage all over the internet.

On August 18, 2020, Netflix released a promotional poster ahead of the release of the film Cuties (Migonnes), on its platform. The award-winning coming-of-age film was inappropriately marketed by Netflix through a poster which featured scantily clad young girls.

An online petition garnering over 200,000 signatures, urged Netflix to remove the movie from its platform. The movie based on the life experiences of the director Maïmouna Doucouré was actually heartwarming. There was outrage and the movie received a ton of hate not because of the content of the movie itself, which hasn’t even been released on Netflix, but because of certain assumptions made due to bad marketing.

They have since taken down the distasteful poster, apologized for the wrongful representation, and updated the promotional pieces— but the damage had already been done.

Looking at all these cases, the ones most vulnerable to getting cancelled are those without strong support, and those who perform actions that even a society divided in opinions, condemn.

Cancel culture isn’t necessarily all bad. Giving people the power to hold someone accountable by bringing their unfavourable actions forward so that they don’t do more harm, is and has been very beneficial in many cases. In moderation, it may continue to do so.

Written by Ishita Gaur and Abha Deo for MTTN

Edited by Cynthia Maria Dsouza for MTTN

Featured image by Nayana Dhanya for MTTN

Image sources: yourfaveisproblematic.tumblr.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.