2020 has been unpredictable in many ways. Right from an unforeseen pandemic, to an economic downturn of activities around the globe, this year has put a lot of things into perspective. On a military front, India finds itself locked in a military standoff with China over the icy heights of Eastern Ladakh along the Line of Actual Control or LAC. After the Galwan Valley incident, the sentiment against the Chinese Communist Party has most certainly changed in India. Similar views are shown by the rest of the world too, as many countries reset their ties with China. One of the resetting ties is the execution of Quadrilateral (Quad) Security Dialogue between four countries— India, Japan, Australia, and the United States. What began as a meeting on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York a year ago, translated into a strategy, effectively encountering the growing Chinese threat in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean.

The Malabar series of exercises that have been in effect since 1992 included just the US Navy and Indian Navy in the beginning. Now the scope of such an exercise has increased after the participation of Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force or JMSDF and the Royal Australian Navy joining in recently.

Phase 1 of Exercise Malabar 2020 took place from 3rd-6th November 2020 in the Bay of Bengal, and Phase 2 of the exercise took place in the Northern Arabian Sea from 17th-20th November 2020. In both phases, the complexities of the operation increased primarily in the second phase. The four navies mentioned above engaged in a high-intensity naval operation expanding over four days. Most of these exercises included cross-deck flying operations and execution of advanced air defence exercises by MiG-29K of the INS Vikramaditya of the Indian Navy and F/A-18 fighter jets and Airborne Early Warning aircraft E2C Hawkeye from USS Nimitz from the US Navy. Apart from the advanced surface and anti-submarine warfare exercises and weapon firings are undertaken to improve the interoperability factor among the four naval allies. INS Khanderi, which is an Indian built submarine and P-8I, was also brought into the exercise theatre to showcase the platform’s capability.

However, to effectively counter the growing threat of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) in the Indian Ocean, India will have to ditch it’s Cold War policy and start aligning itself with other countries whose policies are driven along the same lines.

In this article, we explain the deployment strategy, expansion problems and try to underline the importance of securing the Indian Ocean for India’s future in the long term.

THE DEPLOYMENT GAME:

China’s naval capabilities have expanded considerably in the last few years and, in many ways, has been able to outmatch the powers of the Indian Navy. But to the say that this makes the PLAN superior to the Indian Navy is quite a high claim. The PLAN has minimal experience operating in waters beyond the waters of China, and that favours the Indian Navy very well.

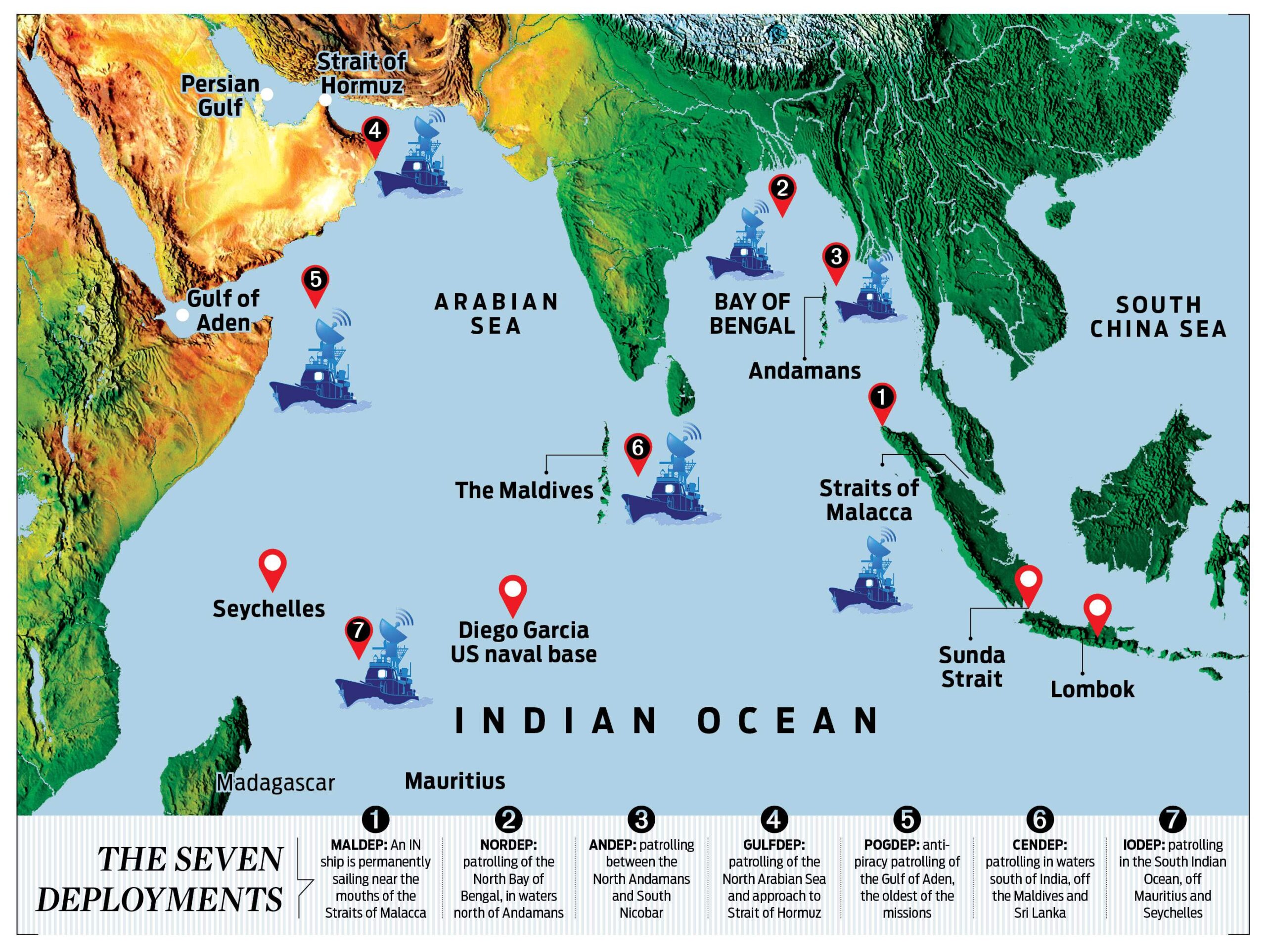

In the last two years or so, the Indian Navy has quickly reoriented itself to become a more cohesive, credible and a combat-ready force in a bid to secure the Indian Ocean. Redirecting towards “Mission-Based Deployments” (MDP), about 15 warships are patrolling seven areas of the water near India and beyond the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and have an eye on all the entries and exit routes to and from the Indian Ocean.

The seven zones are classified as follows:

MALDEP: An Indian Navy ship is permanently sailing near the mouths of the Straits of Malacca

NORDEP: Patrolling of the North Bay of Bengal, in waters north of the Andamans and the coasts of Bangladesh and Myanmar

ANDEP: Patrolling between the North Andamans and South Nicobar

GULF DEP: Patrolling of the North Arabian Sea and the approaches to the Strait of Hormuz and the Persian Gulf

POGDEP: Anti-piracy patrolling of the Gulf of Aden, the oldest of the missions

CENDEP: Patrolling in waters south of India, off the Maldives and Sri Lanka

IODEP: Patrolling in the South Indian Ocean, off Mauritius, the Seychelles and Madagascar.

Apart from that, the Indian Navy has also been deploying its long-range maritime reconnaissance and anti-submarine warfare aircraft, the P-8I with the rarity of flying it until the South China Sea. The P-8I has bolstered the capabilities in terms of surveillance. The Navy just got it’s ninth P-8I last month and is stationed out of INS Hansa in Goa. The other squadron is located out of INS Rajakoli, Arakkonam in Tamil Nadu and has been flying sorties almost every day. Such are the capabilities of the aircraft in terms of broad area, maritime and littoral operations, that it has been used extensively during the Doklam standoff in 2017 and even now in the Ladakh standoff. Impressed by the performance, India is looking to procure another six P-8I under the government-to-government route from the US. Since the induction, the aircraft in 2013 it has flown more than 29000 hours and India has become the second-largest operator of this type.

The Indian Navy warships are deployed year-round and are turned around every three months. They generally avoid sailing through international maritime highways and sail in a zigzag manner to cover more area.

In November of 2014, in Gurugram, Delhi, IMAC or Information Management and Analysis Centre became operational. It is the nodal centre for maritime security information collection and tracks every non-military ship or commercial ship passing through the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). The Directorate of Naval Operation (DNO) follows military vessels on a classified network. The ships deployed in the seven areas of the Indian Ocean collect and pass information to both IMAC and DNO. At the centre, IMAC can look up at any ship in the IOR and can collect all sorts of information as to where a ship is headed or how many Chinese vessels are in the Indian Ocean or even check if the identity of the ship is the same etc. IMAC’s main function is to exchange maritime security information among the stakeholders and generate a common operational picture.

RAISING THE STAKES:

In recent years, China has been making its military presence felt in the Indian Ocean. Although Beijing has officially rejected the theory of China setting up overseas naval bases, former PLAN officials say otherwise. Their logic is that if the US can set up overseas bases, then what stops China?

While they continue to violate into waters of Japan and Taiwan, PLAN has been busy increasing their training missions duration and have been moving increasingly towards west, i.e. IOR, seemingly for counter-piracy. Somehow this move coincides with the rapid growth of Chinese presence in Africa in terms of economic prospects. What started as a logistics support unit in 2017, the military base in Djibouti has grown quite considerably. Lately, it has been upgraded and modernised into a naval base with a 1,120 feet pier qualified for housing a Chinese warship and even the Liaoning aircraft carrier. With the follow-up, the Chinese have also built an artificial island in the Maldives, right in India’s backyard. Apart from that, if rumours are to be believed, then Gwadar port in Pakistan has been on a militarising spree. Recent pictures from satellites show that anti-vehicles berms, security fences, elevated guard towers and more. Even more so, reports of China offering to build a naval base at Cox Bazar in Bangladesh is powerful.

Covering an estimated area of 250,000 square feet, the Djibouti base is no ordinary compound and hints towards that it is definitely a military base. Capable of holding an estimated 10,000 troops in the underground quarters and is complete with outer perimeter walls is even more proof of the undeniable truth. While Beijing has maintained that the project is a “support facility” for anti-piracy missions in the African region, there is every evidence to back this claim. Now China’s anti-piracy contingent comprises guided-missile frigates, advanced destroyers and special operation forces, indicating that these contingents are more for power projection rather than anti-piracy operations. Even more ironic is that in recent years is that Chinese submarines have also been spotted accompanying these anti-piracy contingents. Under this guise, the Chinese submarines have spent a lot of time understanding the Indian Ocean.

The vague nature of Chinese naval warship deployment in the IOR foreshadows a larger picture whose hidden significance will be evident in the years to come. A common hypothesis has been proposed as “String of Pearls”. Under this theory, and by recent actions of PLAN can be accepted as a competent hypothesis, is that China is creating a network of artificial bases along the northern rim of the IOR with the idea of dominating the international shipping lanes. Via this network, Beijing aims to provide itself leverage for power projection in the mostly peaceful IOR, a capability it didn’t possess before. Through a massive and successful shipbuilding program, the creation of a fourth fleet, apart from the three, i.e. North Sea, South Sea and East Sea fleets, dedicated to the IOR alone, seem to be very much on the table. The fusion of both economic and military strength in the IOR will provide a substantial strategic footprint to China.

THE FUTURE GAME PLAN:

Admiral Sunil Lanba, the former Chief of Staff of the Indian Navy, once said this in 2018: ‘As far as the Indian Navy is concerned, we have only one front. And that is the Indian Ocean. We have overwhelming superiority over the Pakistan navy in all fields and domains. In the Indian Ocean region, the balance of power rests in our favour compared to China’.

There is much truth to this statement and yet so much to be done to counter the threat looming over the horizon that remains, i.e. People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). Splurging on sea power, a way has been paved for China to change the balance of power in the South East region in its favour. Apart from that, China has also been involved in a number of bilateral and multilateral exercises with the Pakistan Navy off the Makran coast. Since none of these poses a threat to Indian Navy assets, any sea denial won’t work, and the PLAN has cleverly avoided any confrontation with Indian warships while expanding itself in the Indian Ocean.

The Indian Navy has also been on its own version of splurging spree as well. They have been upgrading the facilities in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands as a station to monitor the Chinese activities and also into development of an integrated surveillance network. All of this gives India an advantage in terms of tactical level. But given that most of the Chinese warship deployment is outside Indian waters and since many countries see oceans as a shared space, the idea of sea denial wouldn’t work in this case. The Chinese notion of deploying in Karachi or Gwadar or modernising plans of ports and navies of Pakistan, Vietnam, and Bangladesh wouldn’t be much affected by such tactical measures. India’s slow pace of modernisation of its armed forces has affected the capacity in a way that it can act as a deterrent in this part of the region, especially when it comes to the Navy.

For a successful countermeasure, India must come up with a better plan to combat the Chinese Navy. New Delhi must shed the idea of it’s Navy being a “security provider” and instead project itself as a force to be reckoned with. Taking advantage of the logistics support agreement and working closely with navies of the United States, Japan, Australia(recently), Singapore, Vietnam, and Indonesia can help reshape the balance of security in the Pacific. Acceleration of indigenisation of naval platforms in terms of aircraft carriers and nuclear-powered submarines also goes a long way in securing the Indian Ocean.

Undoubtedly, the answer of Ladakh’s standoff lies in the naval domain, where we still have the upper part but a fast receding capability.

Sources: New Indian Express, The Print, ORF and CSS Analyses

Written by Vaibhav Aatreya for MTTN

Edited by Sanjana Bharadwaj for MTTN

Featured Image from https://www.naval-technology.com/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.