The world, as we know it, is ever-evolving. There has been a transformational shift in the way markets function. Marketers and inventors create brands and offer products or services to meet new demands. However, marketers have often designed products that customers do not accept. Inventors have often stumbled upon game-changing inventions without any intent, to begin with. The question then lies in what marketers and inventors do with products that turn into rejects and misfits.

Somewhere along the way, creativity led innovators to adopt a strategic approach. Instead of altering the product itself to match customers contemporary demands, psychology is often reversed. They focus on changing product functionality, and thereby customer perception, to receive acceptance for the same failed or obsolete products. Inventors also market and create a use for products that emerged without their anticipation.

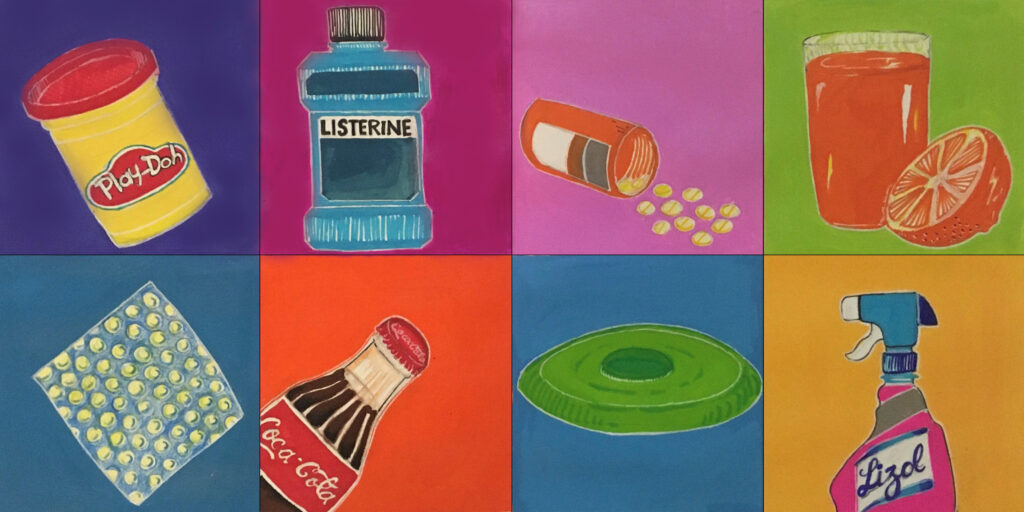

Several brands and products that are popularly known and used globally actually have their roots tied in an accidental creation, or a metamorphosed functionality. Let’s take a look at some of the lesser-known backstories of these popular brands below:

Play-Doh

Play-Doh’s story can be traced back to the 1930s. Kutol, a soap-making company in Cincinnati, Ohio, was nearly out of business at the time. Before their downfall, their main product was a wallpaper cleaner. Since most homes were heated through coal, wallpapers ended up coated with a layer of soot. This created a vital requirement for Kutol’s wallpaper cleaners. For about 10 years, their business was a tremendous success. However, eventually, coal was replaced by oil or gas furnaces. The soot problem no longer existed. When vinyl wallpapers that could be easily cleaned made an entry into the market, sales plummeted further.

The company had another shot at victory when the sister-in-law of Kutol’s owner made a brilliant observation. The wallpaper cleaner Kutol was selling could be used to make decorations and for modelling. It also carried an added bonus; kids enjoyed playing with it. The company then decided to rebrand its product, and alter its intended usage for the market. Their first move was to eliminate the detergent, adding colouring and an almond scent to their product. They positioned the product as a toy in the market, calling it “Play-Doh.” Then began their journey of selling the Play-Doh to schools and stores, after which it became the definitive coloured clay that we know and love!

Listerine

Listerine, the ubiquitous mouthwash, was actually named after a doctor called Joseph Lister. He discovered the importance of sanitation of tools and hands before surgery in the late 1800s. He observed that about half of his patients died of sepsis after amputation. The possibility of death was reduced to a great extent after he began washing his hands and tools. Eventually, this brought him to the realisation that germs were in fact, real and afflicted everyday human life. Lister’s discovery led to the transformed usage of antiseptics in medicine.

One of the first few antiseptics was made by a businessman and chemist named Jordan Wheat Lambert. This antiseptic was named Listerine. They then began to market it as a jack-of-all-trades product—with its uses ranging from curing dandruff, aftershave, floor-cleaner, to even treatment for gonorrhoea. However, they were unsatisfied with the product sales and decided to devise a new marketing strategy. The strategy emanated from an obscure Latin phrase—’halitosis’, or bad breath. The term made consumers believe that bad breath was a disease to be feared. Their marketing campaign and advertisements ideated that bad breath would make a person unpopular. Bad breath was “inexcusable” but could be “instantly remedied” through the use of Listerine. The campaign was ultimately an extreme success, which explains Listerine’s market position in the present-day. Interestingly, marketers later began to use the term “halitosis appeal” when referring to the use of fear, to sell a product.

Penicillin

Penicillin, one of the world’s most widely used antibiotics, was discovered in 1928. The catch lies in the fact that its discovery was accidental. Sir Alexander Fleming, the founder of penicillin, was not looking for what he stumbled upon. He had taken a vacation, and upon his return to the lab, he began to observe some cultures of Staphylococcus. These bacteria cause boils, sore throats and abscesses. He then recorded an unusual happening in one petri-dish—there was a mould growing in the dish, surrounding which there were no bacteria colonies present. However, the rest of the petri dish was lined with bacteria colonies. The mould was later found to be a genus of Penicillium Notatum. Fleming later also understood that mould from the petri dish could kill a gamut of harmful bacteria. He attempted to derive the pure form of penicillin from the dish but found it to be unstable. He stopped researching penicillin after 3 years, in 1931. However, his work led other researchers in the right direction, which allowed penicillin to revolutionise the course of medicine.

Orange Juice

Orange trees were first planted in San Diego in the late 18th century. These oranges were barely consumed at the time. However, nearly a hundred years later, immigrants inhabited the land in search of gold. Amidst their investigation, an odd 10,000 of them contracted Scurvy. Vitamin C-filled oranges were the perfect solution available closeby. Despite this demand, it took another 100 years for commercial production of oranges to be viable and take off. The orange groves continued to grow tons of oranges that were wasted and of no value.

In 1907, a marketer named Albert Lasker was hired by the California Fruit Growers Exchange to assist in the improvement of oranges sales. Albert Lasker found that on average, a person only ate about half of an orange in a single serving. Lasker then initiated the idea of selling the juice from the orange instead of the orange itself, as it would take at least 2-3 oranges to get one glass of juice. The sale of orange juice skyrocketed soon after. Not only was a new product launched in the market, but a daily morning habit for Americans was born too.

The success of Lasker’s idea was credited to the tagline that he used—“Drink an orange.” Advertisements aligned with the tagline, making viewers feel like they were consuming fresh nectar from the source!

Bubble Wrap

The oh-so-satisfying feeling of pressing into and popping bubble wrap is an unusual but

universally loved act by people of all ages.

During 1957 in Hawthorne, New Jersey, engineer Alfred W Fielding and Swiss chemist Marc Chavannes experimented with sheets of plastic; specifically, shower curtains. They aimed to create a kind of textured wallpaper by trapping air in between the sheets and sealing it to create a bubble-like pattern. They had ample ideas for its uses— over 400 of them—and potential and were even given patents for it. The result, however, was undesirable to the intended market, and they decided to sell their creation as insulation for greenhouses. That idea, too, failed as terribly as the original one, as it was rendered ineffective.

In 1960, they founded Sealed Air Corp, to continue developing and finding a viable use for their product, which was now branded as Bubble Wrap. Its usage as a protective layer was discovered by a marketer at Sealed Air Corp, Frederick Bowers. IBM announced its new 1401 computer and needed a way to ensure the safe transportation of its fragile units. Bubble wrap was pitched to them as an alternative to crumpled-up newspaper and was thus used. The venture proved successful; the brand grew and diversified it’s products-like incorporating itself in food packaging—and with it, turned a profit.

Coca-Cola

This immensely popular carbonated beverage, too, was an accidental creation brought about by pharmacist and chemistry enthusiast, John Stith Pemberton, in 1886.

After an injury in battle, he became addicted to morphine. This led him to devise experiments to find opium-free alternatives to curb his addiction. He concocted a syrup-based product made from coca leaf extract and wine. He marketed it as an invigorating and calming ‘brain tonic’ aimed at curing headaches and hangovers, and called it “Pemberton’s French Wine Coca”.

Due to Atlanta’s prohibition in 1885, Pemberton was forced to create a non-alcoholic, watered-down variant of his syrup to meet its popular demand. Once, instead of tap water, carbonated water was accidentally added to the syrup. This new, better creation was then marketed as ‘Coca-Cola’.

Marketers constantly spruced up the recipe and packaging to grab their customers’ attention—bright red barrels to uniquely-shaped bottles with a closely guarded recipe.

The idea of bottling the drink up boosted its popularity too. It still is one of the most well-known carbonated drinks in today’s world, with the trademark being virtually unchanged since its creation.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/0d/5f/0d5f70a0-1d68-4991-b552-733dd3190920/tonic.jpg)

Frisbees

In 1871, William Frisbie launched the Frisbie Pie Company. College students used the pie tins to play games, throwing them back and forth amongst themselves.

That’s where the name ‘Frisbee’ originated from; a name that was apparently disliked by the person regarded as the inventor of the modern frisbee—W.F. Morrison.

In 1937, Morrison and his spouse were throwing a disc-like metal tin to each other, when a passerby offered them a quarter in exchange for the tin, which barely cost a nickel. This event led to the realization that they could make a business out of selling throwable tins, and could turn a massive profit. Morrison produced more tins and sold them in beaches along Southern California, until World War II. He worked on the design, marketed it as the “Flying Saucer” and sold them with his business partner, Warren Franscioni. In 1957, Morrison sold the rights of his new and improved design to an up and coming toy company called ‘Wham-O’.

They marketed the product creatively, using its likeness to a UFO as a selling point, and promoting disc-throwing as a new sport and a must-have beachside carry-on. They changed its name to Frisbee, after the aforementioned pie company. The product’s popularity soared with the rebranding and marketing. The design patented today is a modern version of the idea perfected through tweaks in the original design and changes in the material.

Lysol

Lysol antiseptic disinfectant was first marketed in Germany in 1889 as a method to help end a cholera outbreak. Quite understandably, in 1918, it was advertised as a way to fight an influenza pandemic and was released to hospitals to help disinfect their environment. However, it was in the 1920s that advertisements for Lysol took a turn.

In order to expand their consumer base, the adverts targeted women, blaming any loss of romance after marriage on feminine hygiene. They suggested that women wash their genitals with this product to maintain their “dainty, alluring femininity”. Under all these ads, though, lay the actual target—contraception. They expected women to use these to clean themselves up after engaging in sex as a way to prevent pregnancy; it was, of course, effectively useless. Birth control methods were expensive and difficult to acquire, partly owing to the fact that there were laws against it in several US states. Of course, the next best option would be to use this heavily advertised product.

These ads, riddled with disinformation, actually led Lysol to be the leading feminine hygiene product for decades. The original Lysol solution contained cresol, a compound that causes severe burns, inflammation and death. Hundreds of women met these problems or their demise.

Thankfully, in the 1960s, with birth control legalized and false information debunked, Lysol was and has been advertised as just a home disinfectant.

Markets and marketers grow smarter and more creative with each passing day. Like Fielding and Chavannes—the creators of bubble wrap—they tweak their product and imagine hundreds of uses for it, hoping that perhaps they’d hit a jackpot someday.

These accidental gems grow rarer by the day, making each product’s story all the more fascinating; more valuable. Some products are meant to undergo a paradigm changes—to adapt to changing times, or sometimes simply to make profits!

Written by Ishita Gaur and Sanam Lulla for MTTN

Edited by Avaneesh Jai Damaraju for MTTN

Featured Image by Ribika Basu for MTTN

Image Sources: Smithsonian Magazine, Huffington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.