Art has been a fixture for much of human history. It allows people to communicate abstract notions regarding their worldview by highlighting certain facets of reality or by depicting truths in fantastical forms. The structure for this subtext, however, lies in the narrative a creator chooses. This narrative can be fictional or non-fictional.

History has found itself an inspiration to many people writing books and making films. With the creation of media such as The Imitation Game (2014) or The Big Short (2015), history is portrayed and recast to be consumed by a new audience. While it might be made with good intentions, this recreation of a piece of history comes with caveats—mostly having to do with the facts that the creator may alter or omit to suit their need.

Purpose

At the core of this line of argumentation lies the purpose with which a person makes a piece of media. To make a documentary or journalistic piece would be different than to make a historical drama, even if the lines are blurred. The purpose of a documentary or documentative novel would be to show an event or series of events exactly as it happened, with empirical reports of the same. This can be seen in books such as Ghost Wars by Steve Coll of The Panama Papers by Bastian Obermayer and Frederik Obermaier.

A historical drama, on the other hand, would expect to entertain as a primary objective.

Therefore, these amendments or omissions may come to save time, or to enhance character development for the sake of entertainment, or because it simply wasn’t necessary to show. For example, in the Broadway musical Hamilton, the eponymous protagonist is shown to be remorseful of his affair with Ms Maria Reynolds before declaring it publicly to save his political career. In reality, there was no evidence of this remorse or guilt—if anything, the real Hamilton is suspected of having been even more salacious and committed more adultery. This would have come across as an unlikeable characteristic and might have lost the audience’s interest in the character, this being despite the show’s efforts to portray Hamilton as an underdog for the prior hour and a half.

Another example can be seen in HBO’s Chernobyl (2019), wherein the hundreds of nuclear physicists who helped contain the disaster were represented by the fictional character Ulana Khomyuk. It would not have been possible to coherently introduce and flesh out every one of the scientists and so liberty was taken in creating a new character.

An artist would thus have no debt in their creative space. The person making a piece of art has no obligation to write or create an exact replica of real events, as it is not meant to be educational. Seeing as they would likely have a better handle on the nitty-gritty regarding their art form, the artist would know best what would enhance a narrative and mirror their intended themes. This is not to say this would always achieve critical acclaim. The creator would also have to understand the audience’s paradigm on the matter. This leads to the second constructive.

Audience Engagement

Appreciation for the content

The uncanny valley can be found across any form of art and becomes especially important in terms of revisionist history. If a piece of content is especially fictional and bears close to no resemblance to reality, it would be easier for an audience to consume it. The same is true for content that has zero deviation from the facts. There is, however, an area where the content is too realistic to be seen as a caricature but has digressions that make it unbelievable as real.

The reason the uncanny valley becomes important while talking about films and books based on history is that the same phenomenon extends into the audience’s perception of the truth in the media. If a story seems factually correct but makes changes that affect the flow of the story, it has a chance to seem unsettling.

Going back to the example of Chernobyl (2019), the ending comes across as ham-fisted and strange. This is owing to the fact that the ending has Valery Legasov publicly confronting and shaming higher-ups in the USSR for not investing in safety at the trial of Anatoly Dyatlov. In reality, Legasov was not present at the trial and did not give a speech blaming the Soviet Union in part for the catastrophe. The juxtaposition of the fantasy that a man would be so brave as to dismiss threats from the KGB with the realistic representation in the rest of the series was off-putting. This is because the change placed the show in the uncanny valley of truth.

Gateway to Education

An audience may or may not have an appreciation for the novel or movie owing to the uncanny valley of truth, but these liberties may help the media act as a gateway to being more informed. An interesting narrative whose appeal may be helped by creative liberties would aid the audience’s interest in choosing to research the characters in question.

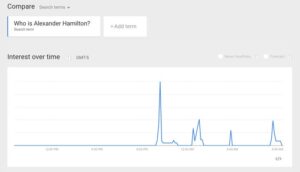

According to a report by Business Insider, the searches for “Who is Alexander Hamilton?” went up by four times following the performance at the 2016 Grammy Awards.

The name of the media need not be the only aspect that leads people to read more. The controversy surrounding factual inaccuracies may also tempt an audience to do research, even if only to spite the film or novel. This is not limited to historical drama, but extends to any show or film or book that attempts to display verisimilitude—the Netflix show 13 Reasons Why faced severe backlash after claiming to accurately portray mental health issues but heavily romanticising and oversimplifying the same instead. The conversation about mental health became a focal point across social media and was covered in the mainstream media as well. For all its flaws and inaccuracies, 13 Reasons Why ended up creating a conversation—even if not in the way it intended.

Glamourisation

The liberties that are taken by the author or filmmaker in creatively channeling real events put the audience in a receptive frame of mind. While an artist is under no obligation to exactly replicate a series of real-life events in their rendition of it, it is argued that art that takes inspiration from historical events must manifest the consciousness of it.

In such ideas that involve the streamlining of fiction and fact together, the depiction of certain incidents and characters may come off to be somewhat falsified or exaggerated to the extent that may take away from the real objective of presenting the novel or movie. The delineation of certain characters, especially in biographical films of eminent personalities, gravitates back to the need for validating historical authenticity. Many filmmakers resort to glamourisation or twisting of certain plots in order to keep the audience engaged, and at times, to suit the commercial markets.

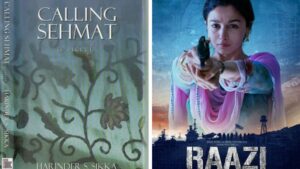

Bollywood movies such as Raazi, based on the life of an Indian spy, Sehmat Khan, and Gunjan Saxena: The Kargil Girl, a recent biopic on the Indian Air Force officer, have been the subject of conflict. The former was said to have had a modified ending to appease the audience, contrary to the novel it was based on, Calling Sehmat. This movie grabbed the ubiquitous crutches of Bollywood— emotion and drama, all the while sending a powerful message. Many critics claimed that the fixation on the well-intentioned message diluted the complexity of the film. The latter, however, got many people to express their concerns regarding its accountability. This movie is said to have proffered wrong notions about the Indian Air Force, where fiction weighed heavier than fact.

Another example would be the biopic of Stephen Hawking, The Theory of Everything. Despite the film being based on the memoir of Jane Hawking—Stephen Hawking’s first wife—it digresses from its source so much that it is said to have dishonestly represented their marriage. This is alleged by Jane Hawking herself. A rearrangement of facts to suit the dramatic conventions is evident upon contrasting with what can be found in the memoir.

The conversation involving factual accuracies and historical authenticity always remains a topic of debate. The purpose, mode, and method of representation should essentially be made clear in this matter. Regarding the biographies of historical figures who have largely impacted the people around them, and their works are involved, the creators of art must consciously establish the truth, albeit within the permeable boundaries of historical fiction.

Reader’s and Writer’s Responsibility

To know that fiction is a key element in the genre of historical fiction remains paramount. To be overly critical of this genre and restricting artistic liberties is unfair solely because the unconditional replication of real life is not what makes fiction.

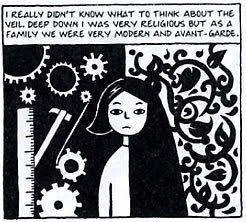

Arguably, even an autobiography can not be completely accurate, because it only presents one side of the story and not all events can be remembered accurately. For example, Persepolis is an autobiography of Marjane Satrapi that describes her life in Iran, during and after the Islamic Revolution. The oppression suffered by the Iranians, mostly attributed to the ruling ideology that pits the power of the state against the individual citizen, remains the central theme of this account. The focus of this autobiographical account is the civil rights agenda and the sense of individualism. Still, it leaves out the class struggle that formed the background of the Iranian Revolution, the narrative of Iran’s class struggle. It was said that this account comes off as a case of partial history being told. However, it cannot be held against Satrapi since this is a firsthand experience of life in Iran at that time.

A novel or film having historical fiction at its core must have a balance between fact and fiction, not taking away the sense of creative liberty and rearrangement. However, it goes without saying that it is vital to connect the audience to the tangible things from the past, to weave a world that seems real. The reader must be informed enough to make a judgment of what cannot be completely accurate. It is both the audience’s responsibility to understand the difference between a documented historical account and a work of historical fiction and the creator’s responsibility to add the element of truth to make the story intriguing yet believable.

Essentially, creative liberty and departure from cold fact is not a bad thing. It helps tell a better story and does just enough to make people wish to learn more. A piece of media that digresses but captures enough attention and sparks enough interest to elicit a google search is one that has helped the audience.

Written by Varun Vyas Hebbalalu and Radhika Taneja for MTTN

Featured Image by Varun Vyas Hebbalalu for MTTN

Image Source: opindia.com, Business Insider, The Complete Persepolis, Google Images

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.