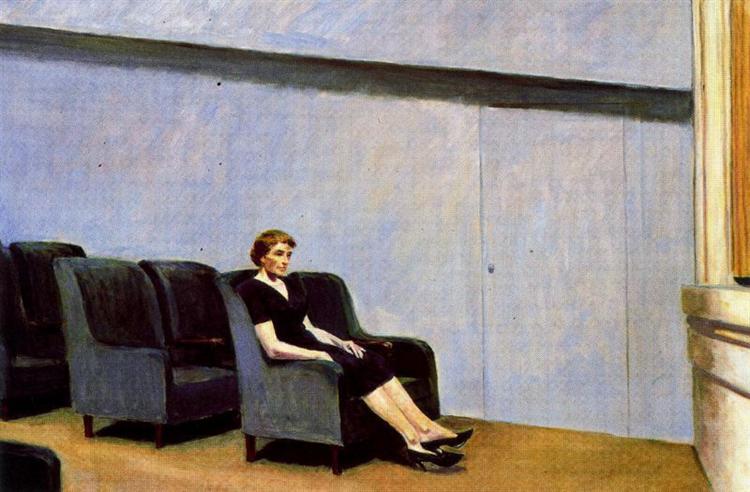

In the midst of countries locking down and people growing more distant owing to the Coronavirus pandemic, Michael Tisserand tweeted, “we are all edward hopper paintings now”. The comparison seemed uncannily apparent with Hopper’s paintings depicting voyeuristic canvases—that imbue a sense of loneliness and alienation. It can be argued, that not only the fear of imminent danger but the isolation that comes with quarantine and other measures necessary for precaution are responsible for the debilitating state of the populace’s mental health.

This is not to say that such steps are not to be implemented. However, understanding the circumstances surrounding one’s reclusion would play a significant role in combating issues of cabin fever and potential depression.

we are all edward hopper paintings now pic.twitter.com/gpcmSiavkD

— Michael Tisserand (@m_tisserand) March 16, 2020

It would be pertinent to analyse the same in terms of two paintings—Thomas Moran’s Autumn Afternoon, and Edward Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning.

At first glance, the two paintings shown above may seem randomly chosen. The juxtaposition of the two— however— can be seen as a deconstruction of urbanisation. While not visible directly in the subject matter, we can mark the paintings beyond the canvases, as reactions to times of turmoil and crisis in the United States of America. Thomas Moran created the piece while the North and South fought in the American Civil War (1861-65), and Edward Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning was made during the Great Depression (1929-33).

Autumn Afternoon seems more irenic and serene. The rural American wilderness captured— as if rejecting the rapid industrialisation of cities and towns. In this painting, the solitude is something to be doted on— making the point that seclusion maintains the purity of the scene. Any hint of human encroachment or reference to the ongoing war would have gleamed an observer’s attention. In essence, it seems that the painting speaks that a lonesome retreat from the events that were unfolding is idyllic.

On the other hand, it is this lack of human engagement with the background that makes Early Sunday Morning that much morose. One sees buildings, shops, and homes— but nobody to inhabit them. The painting suffuses a feeling akin to someone opening their fridge only to find a bread slice and a single egg.

This is because of the defamiliarisation of expectations one has for an urban environment. Archetypally, a city is supposed to have a population, and these people are supposed to be dynamic. As we would expect to see an ensemble of food items in a fridge, one would expect to see the bustle of people in a representation of an urban setting. On seeing the morsels of food in the refrigerator, one might feel hungrier, just as an evident lack of strangers would amplify one’s awareness of themselves being in the area. In the case of someone observing Hopper’s painting, this leads to a feeling of isolation and loneliness.

The sorrow is owing to the reminder of businesses that were forced to shut down. The socio-economic climate was one of alienation and desolation, while the world barrelled towards the second world war. Closed doors and empty windows carry with them the idea of the distance between the people.

In this case, the ensuing lonesomeness is one that carries a negative connotation.

Thus, the question arises– why is isolation sound in nature and evil in cities? If anything, according to logic, it ought to be the inverse. In nature, isolation would mean that one would have to fend off predators, gather food, and go about their lives without the comfort of support from peers. Living alone is more comfortable in more developed areas, for the groundwork has already been set, and all that one has to do is essential functions. And yet, the notion of living alone surrounded by greenery is an ideal many strive for.

Herein lies the crux of the argument. The cityscape is built on the premise of human interaction— one must always be productive and engage with others to make up for them not having to guarantee themselves underlying securities and facilities. One feels the constant pressure to be doing something to further a facet of themselves, whether it concerns their career or a hobby or their relationships. Hopper challenges the idea of yielding an output in Early Sunday Morning, and in doing so, he elicits a feeling of discomfort.

This is the problem with urbanisation. The need to move forward supplants personal mental health— due to the rapid nature of development across the planet. People feel like they ought to keep up, even if it comes at the cost of their own mental well-being. A typical day would consist of classes or work or exercise. When the proceedings of a typical day are impinged upon by an unavoidable aberration, it shocks them. When they don’t lose that extra weight or don’t learn a skill at an advanced level, a person would see themselves as a failure.

Societal norms become more predominant in urban culture. The belief that others must live up to a preconceived ideal leaves no room for any idiosyncratic characteristics. Anyone who dithers from an age-old idea of what work constitutes is labelled a ‘bum’ or ‘lazy’. This guilt-tripping has become so inherent that it a large part of why people are miserable during the pandemic.

In the situation of the Coronavirus pandemic, productivity came to a screeching halt when countries were locking down, and people found themselves traversing the same environments daily for months at a time. The guilt of not doing much became internalised to the point where it might have impacted people’s self-image and inevitably hurt their mental health. Despite the advent of technology to the point where nobody truly is disconnected, the internet is inadequate in terms of substituting personal contact. One no longer feels the warmth of companionship and is forced to keep apart for extended periods.

Another facet to the polarity between the connotation of isolation in the paintings is scale. Autumn Afternoon depicts a set that is large and expansive. Any landscape is usually vast as well, whether it be forests or a desert or the ocean. This sizableness comes with a sense of grandeur and freedom.

In a city, on the other hand, one would feel more claustrophobic. With an enormous population density, homes become whatever small apartment or mortgaged house a person can get. To own a site of land in and of itself has become a symbol of status.

To be cooped up in a minuscule area for long periods is bound to have an impact on a person’s mental state. It’s the same walls, same furniture, same things. Homeowners own less and are forced to be satisfied with what they have. The monotony pervades mindsets and can get to people. To be isolated in a small apartment is not nearly ideal as to be isolated amongst flora and fauna.

In conclusion, it is society’s vision of itself and the resulting ideals of an urban civilisation that painted life during the pandemic to be more akin to one by Edward Hopper than by Thomas Moran.

Written by Varun Vyas Hebbalalu for MTTN

Edited by Alankriti Singh for MTTN

Featured image by Edward Hopper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.