Circa 3500

The night was eerie and calm as Ian McStein slid into the cellar. It has been three weeks since his grand-uncle disappeared. The Regime’s functionary said he wouldn’t return, and no sane person would ever question the Regime.

Arthur McStein had not always been a strange man. He was an ordinary janitor who lived alone and worked at one of the research laboratories. One night, the Regime’s policing bots were sighted near his house. Nobody had heard of him since then. The rumours are that McStein had illegally used a classified machine and “witnessed things” which led to his remote execution.

People were curious about what he could have possibly seen that got him killed. But the Regime’s word was final in everyone’s lives; everything they read, saw or experienced was of the Regime’s making. They had no history or identity of their own except the one spelt out by the Regime, and they have been the sole authority for as long as anyone could remember.

Curiosity could cost people their lives. But Ian had to find out the truth.

The metal trapdoor slid open as he made his way down the staircase. His fingers brushed against the cold walls. The cellar was strewn with old, forgotten knick-knacks and objects that had become obsolete decades ago. Arthur was a hoarder.

Ian headed to a decrepit storage rack filled with dozens of paint cans. Thirty minutes later, surrounded by opened cans and splattered paint, he held his stolen laptop with an old key drive plugged into it and began reading.

The Memoirs of Arthur McStein

ENTRY NO. 1

YEAR: 431 BCE

LOCATION: Athens

I think it’s been several weeks since I travelled back in time using the device. By now, the Regime must have found out that I had meddled with their prototype. But I am so fascinated by the world out here that the danger awaiting me took a back seat.

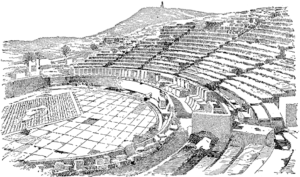

Today, almost 15,000 people gathered together in a colossal seating structure carved out of a hillside which wound around a playing area. It was flanked by stone passageways with a raised platform behind it.

Priests sat in their thrones, their robes billowing in the wind. They bore an uncanny resemblance to the Regime’s seat of power. A shiver ran down my spine, and I had to force myself to look away.

Suddenly, cheers erupted around me as people wearing peculiar costumes filled the orchestra. A single person decked in exaggerated clothing appeared behind us. He donned a mask, and his voice amplified as he spoke.

The people in costume sang and danced till the end. Two more people accompanied the man with the mask; sometimes they resembled the common people, other times the authority. I couldn’t understand their tongue, but their conversations seemed long—detailed and lyrical, clearly evoking strong feelings.

Alongside this event, processions took place, upstanding citizens were rewarded, and slaves were set free. It was an ordinary platform; nothing like the Regime’s impressive buildings. But the citizens could speak—they were loud, wild, and unapologetic of their existence. They complained and even threw fruit if the performance did not please them. And nobody was reprimanded, thrown out, or executed.

It lasted for seven days—the festival of Dionysos Eleuthereus—and each day, the people engaged in conversations. They weren’t equally held in regard by the others, but they were all negotiating and reimagining their identities. I wonder if this could ever be the case under the Regime.

ENTRY NO. 2

YEAR: 1066 CE

LOCATION: Hastings

Time seems to run differently in the past. What I had thought was a several weeks’ trip turned out to be only a second long. Nobody had noticed I was gone. I still consider myself lucky that the Regime’s bots did not discover my secret. But not before long, I yearned to return to that place of wonder.

With a stolen language translator tucked into my ear, I found myself at a starkly different setting this time. From a hilltop, I could see a battle between the Norman-French troops and the English army. I am no stranger to violence, having witnessed public executions of rebels against the Regime. But I was taken aback when the Norman troops broke into a song—The Chanson de Roland — in the middle of the fight and proceeded to win the battle.

I spent the next few days getting to know my surroundings. I watched storytellers who gathered an audience, narrated, and acted out different parts of folklore in a lyrical form. I watched them adapt to suit their individual style and the locals’ preferences. These tales often featured anthropomorphised animals that depicted a standard of human behaviour. What a marvellous way to educate illiterate people on ways to live!

Beowulf was one such story performed orally which seemed hugely popular amongst the listeners. It is the tale of a lone hero hunting down and defeating a dark monster that threatened the people. A sudden realisation struck me—it was the same story adapted as The Song of Roland, sung by the Norman troops, with a crusader threatening people’s cultural lives in the place of the dark monster.

Stories created for mere entertainment had the power to wage and win wars, and I wondered if this could help overthrow the Regime. For the first time in years, I saw light at the end of my people’s dark, lonely tunnel.

ENTRY NO. 3

YEAR: 1350 CE

LOCATION: Florence

During my time here, I hid in an abandoned shed. The streets were empty, and someone was always burying their dead. People left the cities for the villages in a futile effort to escape the plague. They desperately looked for an explanation; some even killed masses to get rid of the ‘heretics’ who they believed brought the disease.

One day, two middle-aged men entered; the younger clutched a bundle of papers tightly to his chest. They looked weary; anyone could tell that they had lost people to the disease. I belatedly noticed the bags—they were here to stay—but my fear of being discovered turned into bewilderment when the younger man began to speak.

“Have you had the opportunity to read The Decameron, Mr Petrarch?”

“No Boccaccio. It is a product of your youth in the quest for a popular readership. It is unworthy of my time, but I did like The Patient Griselda. I translated it to Latin, and some of my friends wept upon reading it.”

These two men were living through one of the worst afflictions to affect humanity— they could possibly die tomorrow! — but they chose to talk about stories and criticise them. Maybe, that is what they needed to survive.

Boccaccio turned pink with embarrassment, but they continued to talk about the stories in detail. They were rooted in folklore I had heard before. I realised when nothing is in control and chaos ensues, stories anchor people’s lives with a little bit of familiarity.

These stories were not mere distractions from reality. People cried over something that could be a lie even when death was rampant outside. It offered them the opportunity to deal with the reality of their situation and hope to overcome the calamity.

My revelation was accompanied by a sneeze so loud; I was sure I had set the Regime’s bots on my tail. I was terrified at the prospect of my actions altering the course of history, but all I heard were screams of terror as the two men left in a bid to escape the ‘plague’.

ENTRY NO. 4

YEAR: 1760 CE

LOCATION: Paris

As I landed in a dumpster in a strange place, a sudden fear engulfed me—the device had begun malfunctioning. I could no longer control it; I was subject to its whims.

I took in my surroundings and found myself facing the backside of a house. Through a crack in the window, I saw a gathering of people who looked quite distinguished in their attire. A woman stood at the door, with an air of importance. She greeted a man—Jean le Rond d’Alembert—who proceeded to converse with her. Through their conversation, I discovered that he was a reputed intellectual in their society.

A man entered the salon whom the hostess—Madame du Deffand—greeted as Doctor Fournier. I was taken aback by his manner of returning the greetings.

“Madame, I am honoured to present you my most humble respect,” To one man,

“Monsieur, I am honoured to greet you,” and to the other,

“Monsieur, I am your most humble servant.”

But, he threw a cursory, “Hello Monsieur,” to d’Alembert.

Despite these men being considered equal intellectually, everyone was constantly reminded of their social status. It became more apparent through the night as only certain people were allowed entry into what I learned was a salon. Every conversation, discussion or reading of stories strictly followed a code of behaviour.

During the event, I overheard a writer by the name of Voltaire conversing with Madame du Deffand about his article Men of Letters. He claimed, “It was more important to be a man of the world than a man of letters.”

The salon was not just a place for writers like him to acquire patronage, or promote their material but also to affirm that they have achieved social success through writing. There were written works read out that stressed on rational thinking, liberty, progress, and constitutional government that night. Still, inside the salon, the hostesses made sure that the guests engaged in only a certain polite way. I could see how stories could break barriers and give everyone common ground, but the writer had to conform to dominant social norms if he needed to share his work or visit the salon. And I puzzled over how it would be different if the writer simply stepped out of that salon.

I slipped from the dumpster on which I was standing and tightly shut my eyes, dreading the fall. But the device had other plans, and I was home before I knew it.

ENTRY NO. 5

YEAR: 1812 CE

LOCATION: Paris

Anyone in their right mind would probably get rid of the device because of its impairment. It could potentially lock me up in an era forever. But I was a man who had tasted freedom and I wanted more.

I landed in the middle of a cobbled street. I could see a vast hall through a window, decorated for an extravagant party. People, dressed in expensive silks, sat around an oval table. A man stood at its head with the face of a hero. He held a pitcher—of what looked like alcohol—in one hand and a woman in the other. He seemed to be reciting something, and the audience clung to every word and each shift of his tone. It took me a moment to realise he was telling them a story—a tale of two lovers— about a man who liked to break rules and a woman who was a staunch follower of rules. He told the guests of their escapades, how they took on the world for their love, and how they lived together happily for the rest of their lives. By the time he was done, the women in the room were in tears, and the men were staring at him in awe.

After a moment of silence, the room burst into cheers and claps. A man called out in a thickly accented English, “Extravagant poem, Lord Byron.” Turning towards the source of the cheer, he took a bow and looked around the room.

“Friends, thank you for your time and your enthusiasm towards my sad excuse of art. For the greatest art of life, is sensation and feeling. To feel is to exist and to exist even with pain is living.” Taking a sip from his jug of wine, he continued. “As you, my friends, kin, and well-wishers are here, today, I present you all with the first edition of my newest collection of poetry. All of you can take one with you, take it home to your wives, husbands, brothers, and sisters, and spread the world of love to them.”

With that, a door opened, and people in uniforms started to pile in with red-bound books — the colour of the manifesto, the colour of our uniforms, the colour of the regime, and the colour of my home.

ENTRY NO. 6

YEAR: 1837 CE

LOCATION: East London

Time is running fast in the past, and I can barely stay put for more than a few hours.

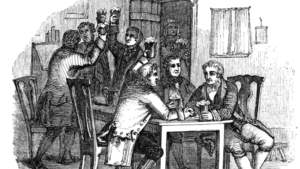

I arrived at a bar and was greeted by the stench of rotten fish, sweaty bodies, and old ale. The old barkeep was ordering around young boys, who scurried past me carrying huge mugs and jugs to sate the men calling for them.

Across from where I was hiding, I noticed a man engrossed in a book. I watched the scene unfold as two men, engaged in conversation, joined him at the table.

“- you don’t think it’s a tad bit eccentric, eh?”

The other, who was gesturing to the bartender for ale, looked back at him and answered, “I think it’s refreshing. The way this character Pickwick has been played out is more human than the flowery nonsensical balls I have to attend.”

“But Pickwick and his companions, what are they called again? Right, Pickwickians! Now they are real lunatics, and if men in this society do the kind of things they do even in a half-hearted manner, it’ll put everyone for a complete season in distraught.”

“So it’s all the more reason to do it. It’ll stop the society mamas from chasing after us to get our legs shackled and give us time to enjoy a little in this drear city.”

“But Robert- you can’t decide how you want to lead your life because of some lunatic publishing seven stories on some godforsaken magazine and you – “

“But Reggie,” Robert said as he stood up, “dear old friend. Live a little, imagine going around town crusading as one of the Pickwickians, how many of those money-mongering mothers will be interested in marrying their daughters off to mental men? Imagine how much time we could buy for ourselves before falling into a lifetime of misery—months, maybe even years. It could be the best decision of our lives.” Taking one last swig of his beer, he got up and started to run towards the door.

“Where are you going?” Reggie inquired anxiously, paying the money and getting ready to follow his friend out.

“To go be a Pickwickian,” Robert said with a mischievous smile and was followed out by a sulky Reggie.

The stranger with the book muttered, “Not a bad name—Pickwicains”, and stood up to leave. The bartender called after him, ”See you tomorrow for a game of cards, Dickens.” Dickens waved his hand in response and went on his way.

ENTRY NO. 7

YEAR: 1913 CE

LOCATION: Baltimore

I don’t know how long I have left before one of the higher-ups finds the device missing. Or before it traps me in the past forever. I wished for one last trip, one final revelation. I tried to set a date or location, but the device started malfunctioning, and I ended up crash landing into a morose and abandoned town. Surprisingly, the instrument was still in one piece. I walked around and reached the town square where five kids were huddled over a book. I hid behind a row of trees and overheard their conversation.

“I wish that I could go fight in the war too,” a little boy whined. “And I wish I could go to a ball as grand as the one Meg went to,” a girl who looked a little older than the boy snarked back. They continued arguing.

“I wish Papa could come back from the war and take us to the carnival,” another girl said quietly.

The girl, who looked the oldest of the lot, kept the book aside. “You know, Martha,” she said, looking at the teary-eyed girl. “We can go to the carnival today. Just run back home, grab your sweaters, and be here in ten minutes! The sooner we leave, the faster we are back before sundown.”

As the kids scattered, my eyes fell on the book that was left on the bench. The pages fluttered in the soft wind, and the words written on its cover, ‘Little Women’, went in and out of my sight.

“You want the book?”

I stood there, terrified. I had been seen. The kind girl held out the book towards me, oblivious to my fears and stuttering.

“It was my brother’s before he was conscripted into the war.” I gently took the book from her hand. “He loved reading, you know, and he always read that book for me before he went to bed. He said he loved it so much because it reminded him that family was more important than anything else in the world. I hope you find your family with the help of this book,” With a hint of a smile, she said, “I have found mine.”

Suddenly, the device started clicking in my pocket, and I could hear the clacking sound of the regime’s bots. Before I could thank her, I was back in my quarters with the tattered book in hand.

I cannot explain why I haven’t been caught yet. Maybe the bots aren’t as smart as we think.

That night, I sat down to read a book that isn’t in the Regime’s manifesto. As I consumed the beautifully written words, I thought of the war-affected families left with only stories and keepsakes of their loved ones. I was overwhelmed with emotion, and my eyes welled up with tears.

ENTRY NO. 8

YEAR: 2022 CE

LOCATION: New York

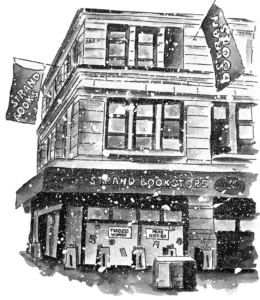

I decided it’s time to dispose of the device. My luck must have surely run out by now. I put it in my bag and headed out. Suddenly, on the way, I heard the familiar click-clacking and unconsciously moved to a small alley. The device was heating up rapidly, and although every instinct in my body told me not to touch it, I did. I was transported to a bustling hub, the dreary sky towering over me.

I looked around and spotted a red-tinted building, with people shuffling in and out the door. The board read ‘The Strand’. I entered, and all I could think about was how much I’m yet to discover. I was, yet again, in another world—far from my own. I was standing amidst books, rows and rows of books. People were free to touch them, sift through them, and take them home if they wanted to.

I approached the first row towards my right and picked up the most colourful book of the lot. The name read ‘Percy Jackson’. Unlike all the other books I had seen, the cover had a bright, beautiful portrait of a boy holding a sword. Next to it was a stash of books titled ‘Harry Potter.’ I made my way towards the next aisle, and by the name of the Regime, I couldn’t believe the title of the book in front of me. It was named—

Ian stood there, dumbfounded. A different kind of world prevailed before — a world where the Regime did not exist. And his grand-uncle had accidentally discovered it. The last entry was incomplete; he must have hidden the logs when he heard the bots approach. Now, Ian was probably the sole bearer of the truth. This information, if used correctly, could change everything about their lives. No more empty seats at dinner tables or crouching when a functionary walked by or dreading another law that would ruin their lives. Ian felt a little helpless, but he remembered his grand-uncle’s accounts. Stories built free spaces, broke down social barriers, gave hope to the lost, impelled and won wars, and brought down tyrannies. Stories could set people free. It was his moment of truth. His fingers rapidly danced over the keyboard as he began to type.

Written by Deepthi Priyanka C and Ramya S Prakash for MTTN

Edited by Tulika Somani for MTTN

Featured Image by Ishaa Sahani for MTTN

Image sources in order: Theatre Architecture, Ancient Origins, Morning Advertiser, Society 6

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.