Content Warning: The following article includes mentions of Murder, Assault, Sexual Assault and Graphic Descriptions that may be unsuitable for certain readers. We advise utmost caution for children under 13.

An all-too-familiar trope in crime shows and a constant source of intrigue to true crime fans, the insanity defence has become a household name. But beyond the dramatic depictions and salacious media coverage, what does it actually mean to be considered legally insane?

The Account of “Unsoundness of Mind”

The insanity defence is a defence that can be pleaded in a criminal trial to be excused of the culpability of the crime committed. The defendant, while confessing to the crime, argues that they should not be held accountable for their actions due to episodic or persistent psychiatric disorder.

There have been countless criminals across the globe who have pleaded insanity to escape charges of varying degrees. To understand the functioning of the defence in a nuanced manner, this article looks into the cases of two of the most infamous serial killers in history. These men tried—and failed—to prove their insanity in court and were given the maximum punishment for their crimes. Despite committing deeds that would make anyone “in their right mind” shiver, they were found sane in the eyes of the law.

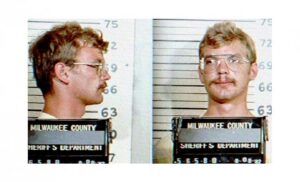

Jeffrey Dahmer — The Milwaukee Cannibal

“You took my 17-year-old son away from me. I’ll never get a chance to tell him that I loved him, have a chance to tell him that I loved him the last time I saw him, which would be a year tomorrow. You took my mother’s oldest grandchild from her, and for that, I can never forgive you.”

These were the words of Dorothy Straughter, mother of Dahmer’s victim Curtis Straughter, coming face to face with the serial murderer at his Sentencing trial in February 1992. Along with the other victims’ relatives, she was allowed to address the court and confront Dahmer.

Between 1978 and 1991, Jeffrey Dahmer carried out the brutal acts of torture, rape, murder and dismemberment of seventeen young men and boys. The frankness and honesty of his confession, open acknowledgement of the wrongness of his actions, and an elaborate, matter-of-factly description of horrific acts (including necrophilia and cannibalism) shocked the detectives and media alike.

His unguarded directness set him apart from other serial killers, giving a chillingly candid look into the thought process of a monster. The only option before his defence was to plead Insanity.

Early Life

Born on May 21st, 1960, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Dahmer (unlike most serial killers) had a seemingly normal, middle-class childhood. However, his father’s continued absence from home due to work and his mother’s clinical depression did contribute to him showing signs of neglect at a young age.

Since his early days, Dahmer had an interest in the dissection and dismemberment of dead animals. This was bolstered by his father, a chemist, who showed him various tricks such as different ways to bleach chicken bones, believing it to be a harmless hobby and childish curiosity. Little did he know, these lessons would be utilised for much more sinister acts almost two decades later.

Dahmer began drinking at age 14, during daylight hours and even at school, describing it as “my medicine”. Due to a lack of mental health awareness at the time, his behaviour was largely ignored by his teachers and counsellors, chalked up to problems at home.

Progression into a Serial Killer

Dahmer committed his first murder at the age of 18. He lured a 19-year-old hitchhiker, Steven Hicks, to his now empty house with the offer of a few beers. Giving in to his sexual fantasies of fully controlling an unconscious partner, coupled with the rage he felt with rejection when Hicks began to leave, Dahmer struck him with a dumbbell on the head several times, leading to his death. The next day, he dismembered the body and disposed of it.

Though this murder heavily shook Dahmer, and though his unaware family tried a myriad of ways (army enrollment, religion, therapy and counselling) over the years to help set his life straight, it would be nine years before Jeffrey started killing again. And there would be no stopping him this time.

From 1987 to 1991, he would kill 16 men, dismembering their bodies, defiling their dignity and performing various experiments on his subjects, both dead and alive. His MO became habitual for him—storing his victims’ remains as trophies and cleaning their blood from his fish tank became mundane rituals.

Finally, on July 22nd, 1991, after he had put countless men through inflictions only fit for hell, Dahmer was arrested in his infamous ‘Oxford’ apartment, practically by chance, where the horrific discovery of his preserved body parts was made. As he lay pinned to the ground by a police officer, he said, “For what I did, I should be dead.”

The Trial

Over the two weeks of his televised Insanity trial in January 1992, a group of psychiatrists was brought in to determine Dahmer’s mental state. The legal question before them was—had Dahmer been in control of his diabolic actions?

The fact that he had kept committing the murders despite losing his job, religion, family support—practically everything—raised the question of how in control he truly was. On the other hand, the 9-year gap between his first and second murders showed that at least at some point, he had had some restraint over his urges.

At the trial, he was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, schizotypal personality disorder and psychosis. The psychiatrists for the defence argued that Dahmer’s violent thoughts stemmed from years of untreated mental illnesses and that he could have had no control over them without psychiatric help.

On the other hand, on the prosecution’s side, Dr Park Dietz argued that while he couldn’t have had any control over his necrophilic thoughts, Dahmer had had a choice in giving in to them. He mentioned that paraphilia in itself is not a psychiatric compulsion. He talked about the precalculated and meticulous nature of his crimes—except for the first two, careful planning had gone into each murder, he had not acted on impulse. He argued that Dahmer had been under the influence of alcohol in each of his murders, this would not have been necessary had his actions been impulsive. He drank to overcome his inhibition to kill. This meant that it was his alcoholism, more so than necrophilia, that had allowed him to kill.

On February 15, 1992, a twelve-member jury declared him legally sane and found him guilty on fifteen counts of first-degree murder. In his final address to the court, he calmly accepted his 15 life sentences.

In November 1994, Dahmer was beaten to death in prison by a fellow prisoner. He was thirty-four years old.

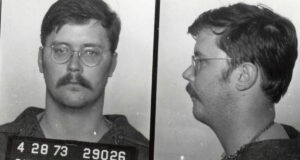

Edmund Kemper — The Co-Ed Killer

“The first girl that’s halfway decent that I pick up, I’m going to blow her brains out.”

Edmund Kemper’s anger towards his authoritarian and allegedly abusive mother had him muttering these exact words before he picked up 23-year-old Rosalind Thorpe and 21-year-old Alice Liu of the University of California in the scenic seaside town of Santa Cruz.

Early Life

Born in 1948, the 6 feet, 9-inch tall Co-Ed butcher was a friendly face at the local watering hole living right under the nose of the local police. He was the helpful local hitchhiker, and with a recognisable car because of his mother’s work at the college, he was able to lure his victims.

Kemper was the neglected middle child of three whose parents divorced when he was 9. The broken family, with fractured relationships with his siblings and an overbearing mother, made things difficult for young Ed.

Erratic behaviour, such as cutting his sisters’ dolls heads, suggested a sort of partialism. It was rumoured that he had killed a family cat that favoured one of his sisters. Often perpetrators practice selecting victims who can be easily overpowered as well as provide for the emotional release they desire. His behaviour worried his mother, and she moved him into a dingy windowless room in the basement as she feared that he would assault his sisters.

In 1963, the nine-year-old boy escaped to live with his father, who ultimately rejected him. He was sent to live with his paternal grandparents in an isolated ranch in North Fork, California. The farm facilitated the realisation of his violent fantasies in small animals.

The problems Edmund had with an authoritative matriarchal figure followed him here as well. After an argument about permission to hunt small animals, fifteen-year-old Kemper shot his grandmother in the head while she was seated at the kitchen table. His ability to process the gravity of the events was so complex that he shot his grandfather to save him the pain the loss of his wife would cause him. This depicts Edmund’s comprehension of the aftermath of his actions.

Owing to the grisly nature of the crime, he was sentenced to receive treatment at Atascadero State Hospital for paranoid schizophrenia. A brilliant 15-year-old, Edmund attained the knowledge of psychometric tests and learned deception by studying his violent neighbours’ results. His necrophiliac tendencies originated from being influenced by violent sex offenders during puberty.

Even after being released from the facility and attending community college with eventual employment, his mother berated him for his abnormality and inadequacy with the opposite gender.

Frustrated and powerless, Kemper decided to use unconventional means to establish control. And so began his murderous spree, raising hell in the idyllic town.

He began killing two hitchhikers every four months and only steered off the pattern to kill his mother, her best friend, and eventually, his own urges to kill.

Kemper began to pick up hitchhiking women. This was initially to demonstrate that he could communicate with them and be treated as an average person. He began to test the control he had over his inhumane urges. As he toured the streets seeking a female, he began carrying a pistol and dared not to use it.

The year-long serial killing employed tedious and personal methods; bludgeoning, strangling and stabbing, which later evolved to shootings for convenience.

Kemper was extraordinarily manipulative and seemed like the harmless, friendly giant, offering lifts to unsuspecting women he often left unharmed when they mentioned the Co-Ed butcher running loose in town. The cognisance of his crimes and their inhumane and illegal nature was all too apparent to him. He showed no sign of remorse until the murder of his mother, Clarnell Strandberg and her best friend, Sally Hallet.

Contentious Confession

After killing these women in cold blood and having his urges purged from his system, something sent him into overdrive. He planned to escape, but something changed his mind when he reached Pueblo, Colorado.

He called the Santa Cruz Police Department and confessed.

The police officers refused to accept his confession as they were unable to comprehend their ‘Big Ed’ was behind the gruesome murders of these women. The familiar face at the local police bars now had a morbid, unheard narrative. Kemper admitted that it was not remorse that conceived his confession but the fear of committing another murder.

The police accepted and recorded his confession because of the great detail and brutal honesty with which he narrated his account to the authorities.

He cooperated with the authorities and remained at Pueblo until he was arrested. Kemper claimed to have disavowed portions of his interviews, claiming that he “did not understand” his reason for murdering people, which he earlier described as a “desire to act out my fantasies…”

He stated that he only told psychiatrists what he believed they wanted to hear and that he exaggerated his acts’ grotesqueness. Kemper’s alteration, however, included a contradiction he claimed to have given doctors “what sounded like a valid excuse” for his murders, but he also claimed to have made up sordid details in order to establish an insanity defence in court.

Edmund Kemper is currently at the California Medical Facility in Vacaville, serving the eight consecutive life sentences he received for the ‘Co-Ed murders.’ He is seventy-two years old.

The cases of Dahmer and Kemper are critical to the development of media coverage of such issues. They also made significant contributions to investigation procedures and criminal profiling. The normality and brutal honesty displayed by the perpetrators provided the leeway for the Insanity Defence to be implemented.

Over the years, thorough questioning over the following aspects has discerned this defence: Who can be determined insane? How does mental illness excuse the accused from criminal guilt? What degree of mental illness constitutes insanity?

In the case of the aforementioned accused, the insanity defence was proven defunct by court-appointed psychiatrists’ diagnoses. In addition to this, the knowledge of the illegality of their actions and acknowledged accountability disregarded the defence.

Written by Anika Shukla and Shirley Asangi for MTTN

Edited by Ishita G for MTTN

Featured Image via Britannica

References: Serial Killers by The Parcast Network, Cornell Law School LII, Britannica, Courtroom tapes and recordings, History.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.