The history of chess is long, complicated and, above all, is constantly contested. I do not wish for you to get lost in this labyrinth and be mystified by some lonely puzzle or worse— get struck down by a crazy axe-wielding, chess-loving scientist in Antarctica which, weird as it sounds, has happened. So we’ll take this nice and slow— let’s set the table for the game, put the pieces in order, establish some ground rules, get the clock ticking, take a peek at chess theory, and watch some serious historical drama games play out. Sounds good? Get a bucket of popcorn. I promise it’ll come in handy.

Just as the last page of your Classmate notebook claims, chess is believed by most people to have originated in India as the game Chaturanga in the 600CE. The pieces consisted of the Raja (king), Mantri (counsellor), Ratha (chariot), Gaja (elephant), Ashva (horse), and Bhata (infantry). Eerily similar, yet not quite like the chess set you stashed in your attic in seventh grade? Well, you’re right.

When Chaturanga spread to other places, it was adopted differently depending on local traditions. For instance, when it spread to China, a certain Emperor got really mad on seeing a figurine representing him in a ‘lowly’ game and killed all the players. To prevent further bloodshed, the poor king became the general. Likewise, when the Muslims conquered Persia, the pieces were made to look abstract as the religion forbade the creation of human or animal statues. Later, when chess spread to Europe from the Islamic world, the pieces’ design retained this style.

The chessboard got its characteristic light and dark squares only in 1090. As strange as it sounds, the game was played on a monochromatic board for over a thousand years. Chess was also periodically banned by the Church from time to time, though this didn’t stop people from trying to find ways to play the game. At one such instance in 1125, an overly enthusiastic chess player— who also happened to be a priest— created the foldable board that looks like two books lying together to continue playing the game secretly. Moral of the story: You’ve got to have faith!

Before the invention of technological goodies, a single chess game could go on for at least 10-14 hours! When sand clocks and watches came to the rescue, a person who timed out did not lose; instead, he had to pay a fine. This gave a whole new meaning to the saying “Time is money”. It also meant that the invention of a chess clock in the 1970s was a welcome relief. As was Bobby Fisher’s design of a clock with an increment that gave bonus time for every move, ensuring that a player in a winning position did not lose because of a lack of time to physically make a move.

We have now covered a lot of details about how chess changed over the years, but are still missing a significant element— or arguably the most crucial person in chess: the queen. Notice that in all the ways in which Chaturanga was adopted, there was no female piece on the board. It was only when Isabella of Castille was crowned queen in the late 15th century that the counsellor became a female piece and could move one step, and later, two steps, diagonally.

However, in 1495, Queen Isabella became the most powerful woman in Europe and astonished the world with her leadership qualities. The queen in the chessboard thus emerged with its sceptre, sword, and crown, and could move freely in any direction. This transformed the way chess was played; it opened up different strategies and quickened the process of a checkmate.

In 1849, a standard for chess sets was designed by Nathaniel Cook and endorsed by Howard Staunton, the world’s best player then, and it came to be known as the Staunton pattern (Yes! The one in your attic!). The oldest surviving complete chess set dating back to the 12th century was featured in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone during a wizard chess match between Harry and Ron.

We’ve now covered the basics of chess history, and how the modern game came to be, but we haven’t covered the much-feared chess theory yet.

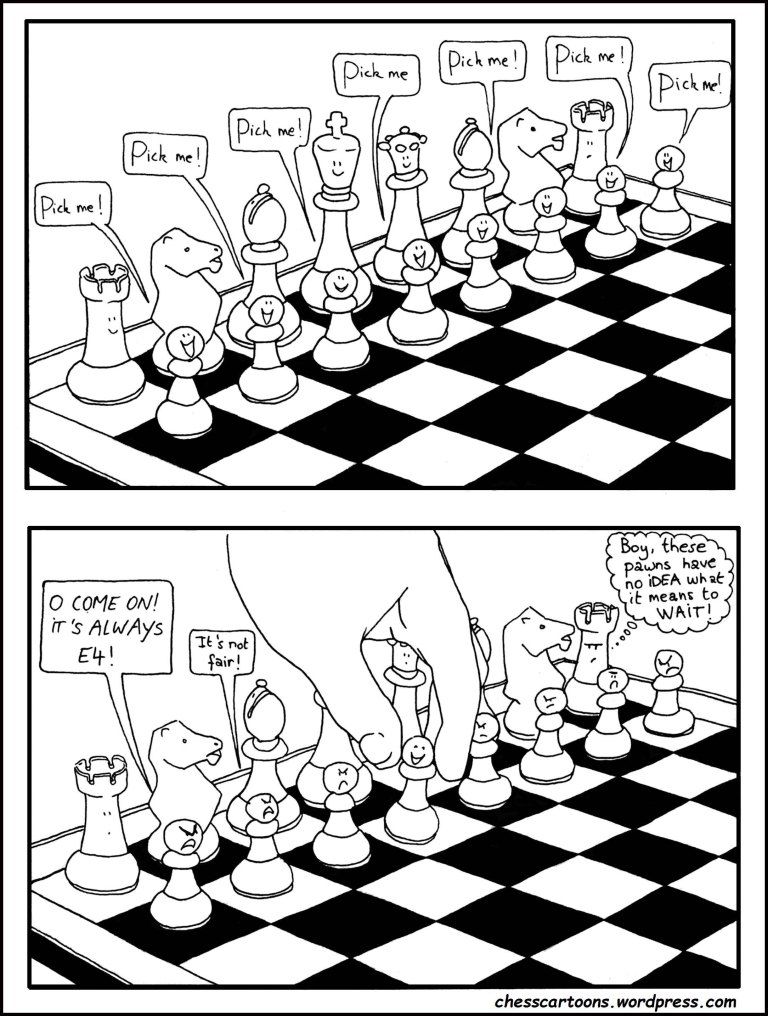

Let me take you back to your first chess class. You are bright, bubbly and optimistic. The coach teaches you an opening that forever becomes synonymous with opening games— e4, e5 takes you down a memory lane and through yet another anonymous match at chess.com. Ruy Lopez analysed this opening in the 16th century, and it was one of the first efforts to form a chess theory. The theory at this point was still primitive; one of the most common strategies used was playing with the sun rays in your opponent’s eyes. No, that’s not a metaphor; it was literally recommended that the sun’s rays fell on your opponent’s eyes making him go on a squinting spree. Chess-kind pretty much depended on sunlight for a while, until the curtains parted in 1749, and Francois-Andre Philidor came through with his book on openings, rook and pawn endgames.

The 19th century saw the rise of the Romantic era in chess. Though the name suggests otherwise, this era did not feature any poetry, serene nature or peaceful games. A romantic chess player would scream ‘Bloody Murder!’ when he saw an opponent, figuratively of course. Chess theory was still developing, and defence as a strategy did not occupy a player’s attention at all. The rule was simple, really: the more bloodshed and violence on the board, the better the game. In fact, Romantic games were also called swashbuckling attacking games as they required players to sacrifice pieces and attack at every given opportunity to win.

Paul Morphy was the John Keats of chess’ Romanticism. A chess prodigy, he challenged and won against every top player at that time— save for dear old Staunton, who declined the offer to play. Morphy was called The Pride and Sorrow of Chess because, despite his exceptional playing skills, he retired at a young age. If this doesn’t convince you that chess is romantic, well, one of Morphy’s best games was played in an Opera House and is titled the ‘Opera House’, even though ‘Morphy Paints the Board Red’ is probably more apt.

When violence and aggression on the board had reached a peak, Wilhelm Steinitz entered the scene. He looked down at the romantic style and used what came to be known as positional play instead. He is credited for being the first to take a scientific approach to chess. His ideas were called the Theory of Equilibrium, and he established the notion that a game leads to a draw when the forces of black and white are balanced. Therefore, winning a game meant balancing these forces over the course of the game, and disrupting them at the proper time to use to one’s advantage. He also noted that checkmate is the ultimate, but not the first objective of the game.

Steinitz was the first official world champion in 1886 and eventually lost to Emanuel Lasker, another positional player in 1894. Lasker is said to belong to the Classical era of chess and is credited to be the first player to use the psychological nature of the game to his advantage by playing inferior moves that confused the opponent. While the romantics attacked every piece ruthlessly, positional players slowly accumulated the little advantages that often miss the eye.

Hypermodernism emerged in the 1920s after World War I, where players took great delight in exposing the loopholes in the theories laid down by the previous generation. Previously, the idea was to hold the centre of the board by occupying it with pawns. Hypermodernism challenged that trend and proposed controlling those spaces (instead of sedentary occupation) with minor pieces such as bishops and knights. Alexander Alekhine is a notable hypermodern player who was known for his versatile style of playing. He could be tactical and aggressive like the romantics or be quiet and calculating like the positional players. This served him well— he not only held the title of world champion for a long time, but he is also the only chess champion to die holding the title.

After World War II, the players that dominated the chess scene from 1948-1972 were from the Soviet Union. The Soviet School stressed the importance of initiative in a game. While hypermoderns challenged the opponents to make the first move, Soviets counterattacked and sacrificed pieces much like the Romantics. Except, their goal was not to attack the king, but to get a positional advantage or eliminate a vital piece of the opponent. In the 1970s the Pragmatists like Bobby Fischer and Anatoly Karpov emerged who recognised that a player could make only a few brilliant moves owing to a shortage of time. Hence a wrong move could determine the course of a game. While Soviets stressed on middlegames, the Pragmatists were inclined towards endgames.

At this point, you’re probably bored of going through theory and are most likely forming judgemental ideas about chess. As a chess-ling, I simply cannot let that happen. So, let’s dive into what happens when vastly different players who had adopted vastly different approaches to the game met. Spoiler alert, a lot of theory happens, and the result is both dramatic and interesting!

The 1972 World Chess Championship in Reykjavik between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky gained a lot of media attention primarily for two reasons. The first being the ongoing Cold War between the USA and the Soviet Union, of which this game was seen as its extension. The second being that the chess scene which had been dominated by Soviet players (save for two) since the inception of FIDE in 1948 (World Chess Federation), was now being challenged by an American player.

Fischer lost the first round and refused to continue playing, claiming that the presence of cameras in the hall distracted him and consequently did not turn up for the second round. After a lot of concessions, the third round took place in a closed room with no cameras. Fischer won and continued to even the score in the games to come. The Soviets were naturally disturbed by the prospect of defeat and suspected that Fischer’s chair was armed with electronic elements or chemical substances that were negatively influencing Spassky. The matter was taken seriously, and the organisers put a 24-hour police guard around the chair as X rays, and chemical tests were conducted. They did find something— a screwdriver and two dead flies. The tournament continued, and Fischer won the World Chess Championship. He was indeed a ‘fissure’ in the Soviet chess wall.

The 1978 World Chess Championship in Baguio City, Philippines is also laced with similar conspiracy theories. Viktor Korchnoi, a defector from the Soviet Union, was to play against Anatoly Karpov, a model Soviet Man. Karpov arrived at the venue accompanied by many people, and one among them was Vladimir Zukhar, a parapsychologist whose sole purpose was to sit in the front row and stare into Korchnoi’s eyes. Full-on creepy. Korchnoi was peeved and convinced that he was being hypnotised and even threatened to poke Zukhar’s nose. Finally, by the seventh game, Zukhar was moved to the seventh row. The tactics did not stop there. Karpov loved eating yoghurt during the matches, and Korchnoi claimed that it was being delivered to him at strategic points signalling a move in the game. But Korchnoi found his yoghurt too. During the week interval between the games, he went to Manila and brought a pair of American yogas (because why not?!) — his to-be lucky charm— and then went on to win several matches and tie with Karpov.

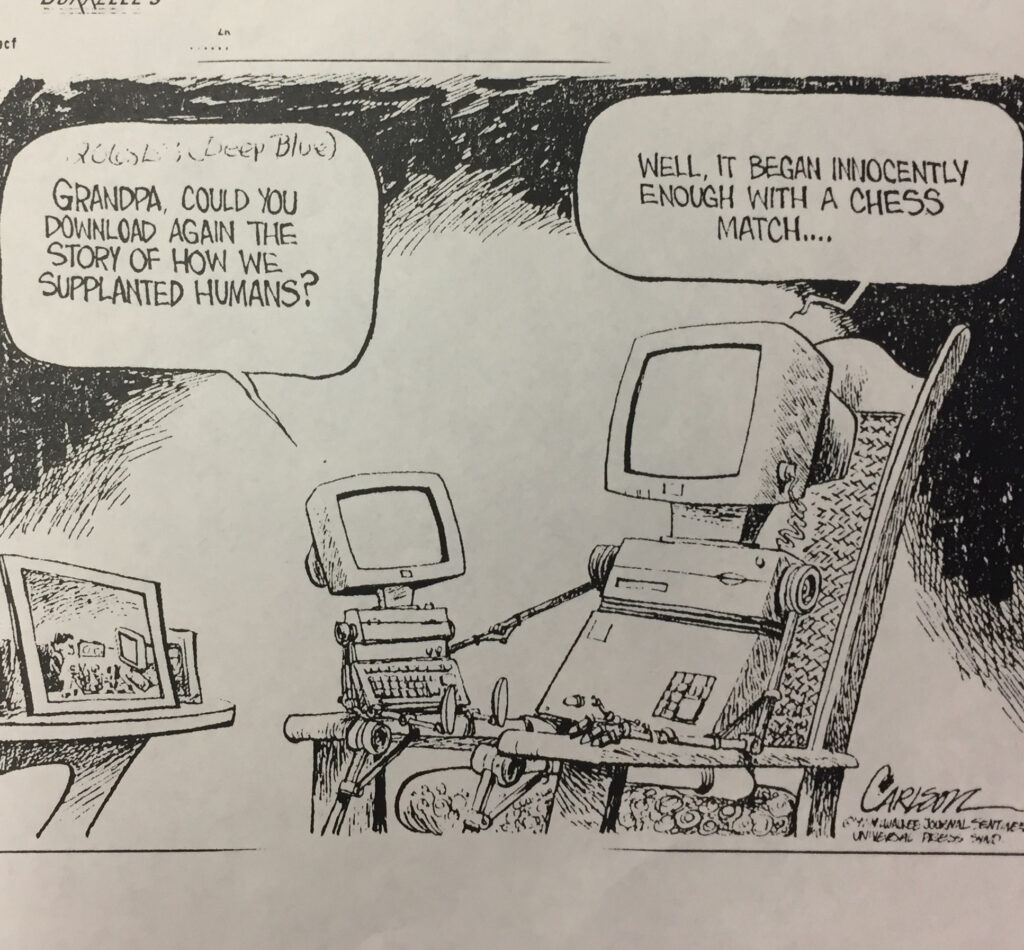

The match between Garry Kasparov and Deep Blue in 1997 was the first time a human was defeated by a computer. Many attribute its victory to artificial intelligence, but Kasparov refused to believe it on account of ‘its human-like’ move in the second game that subsequently led to its victory. He was thrown off so much that he forfeited the game, became overcautious, made three consecutive draws and lost the final one. While IBM claimed that it was a random move due to a computer glitch, conspiracy theories involving human intervention began to arise when Deep Blue was dismantled, and the release of its computer logs was delayed.

Deep Blue was only one of the first of many computers to be incorporated in the chess world— Deep Fritz and Deep Junior still remain undefeated. In 2005, Hydra, a supercomputer defeated Michael Adams (ranked 7th at that time), and computer engines are only growing stronger. Today, they are also widely used by many players to analyse chess theory and improve one’s game. Though, the mystery behind sensing human creativity in Deep Blue and Kasparov’s match still remains unresolved.

So, folks, that is a little something about chess and be sure to read up more or play a game or two— because chess has something for everyone— and that’s why black and white is also a pretty colourful sight!

Written by Deepthi Priyanka C for MTTN

Edited by Naintara Singh for MTTN

Featured Image by Prithvi Shenoy, Timothy Varghese and Goutham Manoharan for MTTN

Images from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, chesscartoons.wordpress.com, and Beaver County Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.