Time has always fascinated the human race. It seems as though those little, narrow sticks that rotate around a circle were puppet masters, in a sense. Everyone ran around all the time – I could hear the hurried breathing, heaving and sighing. It intrigues me for I was caught in the fabric of time like a snag – for a moment, all the humans could see was me. In the bright store lights, in the wardrobe – I was reached for, longed for and loved.

And then, one day, I lay gathering dust – a relic of the past.

A past that came to be approximately five hours ago.

I began as a bolt of cloth in a dingy warehouse and was a brilliant green. Almost as immediately as I was born, I was procured to be made into what I assume was a “shirt”. The lady who made me was shrivelled, her fingers were callused and trembled ever so slightly. They would bleed occasionally, but it would go as soon as it came – and it took her just over an hour to mould me, to shape me. For all the sweat she had poured into it, not one drop touched me.

I was again cast into a dingy place, and to my shock – there were more than two copies of me! It was insulting almost when we were displayed – that I was identical to so many others. There were times when someone would glance at me and walk away, others when they would run their smooth fingers along every seam, even try me on – then look at my worth and walk away. Until one day, she bought me. And I loved every jolt – being chosen, being packed, and most of all, being worn.

While I walked down these lanes, I realised that I had not just been collecting dust, I was slowly falling apart. She reached for me one evening, and a button fell out – the thread lay there, helpless – useless. Then came the inner workings – and I unravelled like an existence headed to doom.

In the corner, the wardrobe whispered goodbye.

I lie now, in a garbage can – or a shiny box. I could never really tell, anyway. The treatment wasn’t all that different.

Source: Bloomberg

The Devil Wears Prada is iconic for several reasons – its cast, its plot – but mainly for the world, it depicts – that of the fashion industry. It was an aloof, almost unreachable place. A runaway with handcrafted garments, an Atelier with an artist and ten craftsmen weaving together something that was a work of art – immortal in its fabrication. Somehow, over time – the craftsman was replaced by the labourer, the artist by a horde of designers forced to create ideas, and the garment lost its magic – it became commonplace.

But what you don’t know is that that sweater is not just blue,

It’s not turquoise, it’s not lapis, it’s actually cerulean.

And you’re also blithely unaware of the fact that in 2002, Oscar de la Renta did a collection of cerulean gowns.

And then I think it was Yves Saint Laurent… wasn’t it? Who showed cerulean military jackets?

And then cerulean quickly showed up in the collections of eight different designers.

And then it, uh, filtered down through the department stores…and then trickled on down into some tragic Casual Corner where you, no doubt, fished it out of some clearance bin.

(Miranda Priestly, The Devil Wears Prada)

The process from runway to stores took anywhere from a year to six months – and the collections held their ground for as long as five years, or even a decade. Now, it is a cumulative total of six weeks – beginning to end, and is born from inhumane labour and ends in the inhumane destruction of the earth.

Advent and Rise of Fast Fashion

The definition of clothing from being a necessity to being a representation of one’s identity in our decade brought about a whole revolution in the fashion industry. In the 1800s, people would have to sew their clothes with homegrown materials. Today, our favourite brand outlets are refreshed with a new trendy collection every week. This raging speed in fashion, better termed “fast fashion” has been the talk of the town recently.

fast fashion

(noun)

(def.) Inexpensive clothing produced rapidly by mass-market retailers in response to the latest trends.

Fashion trends had begun moving at this lightning speed in the 1960s, as young people embraced cheaply made clothing to follow these new trends and reject the sartorial traditions of older generations. Today, the fashion industry leaders are all flag bearers of fast fashion. These retailers can manufacture their collections in as less as three days. These clothes are mass manufactured with cheap synthetic fabric and toxic amounts of microplastics that generate catastrophic amounts of waste, accompanied by unjust labour.

Today’s consumers desire the latest fashions but are not willing to pay the major price tag because they do not hold quality in the same high regard. With this willingness to purchase lowered-quality replicas, the major operators of fashion retail saw an opportunity to capitalize on short-lived trends. And so was the concept of fast fashion born.

Trend Cycles

We all witnessed the return of previously popular fashion trends, such as the Y2K aesthetic. It came with a rage and modernness, and in a way that was more referential and evocative.

Thereby, it is evident that fashion trends are cyclical, with trends believed to return every twenty years or so, giving credence to the “20-Year Rule.” However, with the advent of social media, we have witnessed the emergence of microtrends, with certain garments going out of fashion almost immediately after their emergence. Social media is deciding trends at a breakneck pace, fuelling fast fashion. Trends are sort of like social ideas for a group, community or simply a point in time. They can reflect cultural frameworks, political standpoints, and individual and community identity.

Fashion moves too fast in today’s age. From micro trends to micro micro trends, there seems to be a new aesthetic and mood board birthed daily.

Source: Refinery29

Fashion friends typically come and go in five stages: introduction, increase, peak, decline and obsolescence. According to stylist Samantha Harman, the rise of social media meant that regular folk wanted to be seen wearing something new whenever they posted to social platforms, which increased demand for fast fashion retailers and, ultimately, sped up fast fashion cycles. Louisa Rogers, founder of maximalist sustainable womenswear brand Studio Courtenay, says, “When you combine this constant need for something new for users to engage with and a sense of nostalgia that has a hold on Generation Z (that perhaps feels at least two of its formative years have been robbed from them) it’s less surprising to see styles from as early as the mid-2010s to be reappearing as the ‘latest’ trends.”

Another perspective on why fashion moves so fast today is because there are almost ten times more the number of “personalities” than there were, say, 50 years back. Now, this matters because there are over hundreds of millions of perspectives more today than fifty years back, and those perspectives come with just as many individual ideas, characteristics and personalities. Naturally, the more people, the more opinions that get added to the equation of style and culture within fashion, the more variability there is, and therefore the more distinctions there are in the fashion world. There is so much to choose from in the year 2023; as a result, many variations of trends are taking place among the plethora of subcultures and subgroups.

But Why Is This Bad?

The one major downside to these increasingly shorter trend cycles is the overproduction of clothing. The more clothes that are produced subsequently means more waste is also produced, harming the environment and our ecosystem. This overconsumption of clothing adds to fashion’s huge waste clothing problem, destroying environments as well as the fashion and textile industries locally. Moreover, these fast fashion garments are generally made from fossil fuel-derived plastics, further adding to the environmental and climate emergency through oil extraction, chemical pollution and causing microplastics to leach into soils and seas, degrading the ecosystem.

To understand the rapid turnover of trends, especially in the fashion industry, we need to engineer the idea backwards. A trend is a presentation of ideas – the idea, in turn, comes from the need or the demand to re-invent things or to improve upon the past. You are reading this on some device – a smartphone, a laptop, a PC – or, perhaps, you have it open on a monitor screen. Have you ever looked at the device and truly questioned its functionality?

Why is this particular phone better than the one I had before?

Why is this computer model any different from the ones I have used before?

What purpose do they truly serve?

These questions seem silly, and for the most part, have logical answers. Devices break, and they have upgraded in both the software and hardware realms. Rephrase the same questions for the fashion industry:

Credits: @aestheticskp0p via Twitter

What makes this particular top different from the others?

What purpose does a brand logo serve?

What makes a t-shirt different across new brands?

What is unique about a pair of trousers procured a year ago compared to now?

Most importantly – do you even need them?

Up until the Industrial Revolution, garment manufacture was a cottage industry, and warranted a significant amount of manual labour. Thread, dye, fabric – you name it, and it would all have to pass through a human hand before it even so much as saw a consumer. Naturally, the industry was exclusive: the wealthy could afford new fashions, and the lesser fortunate sections could afford what was availed to them. The landscape has changed since then.

Markets no longer just cater to demand, they create it. This is an approach dating as far back as the 18th century. Hyperconsumerism is a complex topic best understood as an elaborate game of cards with unknown but constantly rising stakes: it is essentially shallow in its aim to acquire goods and provide them with meaning, thus evading the need to procure goods with pre-existing functions.

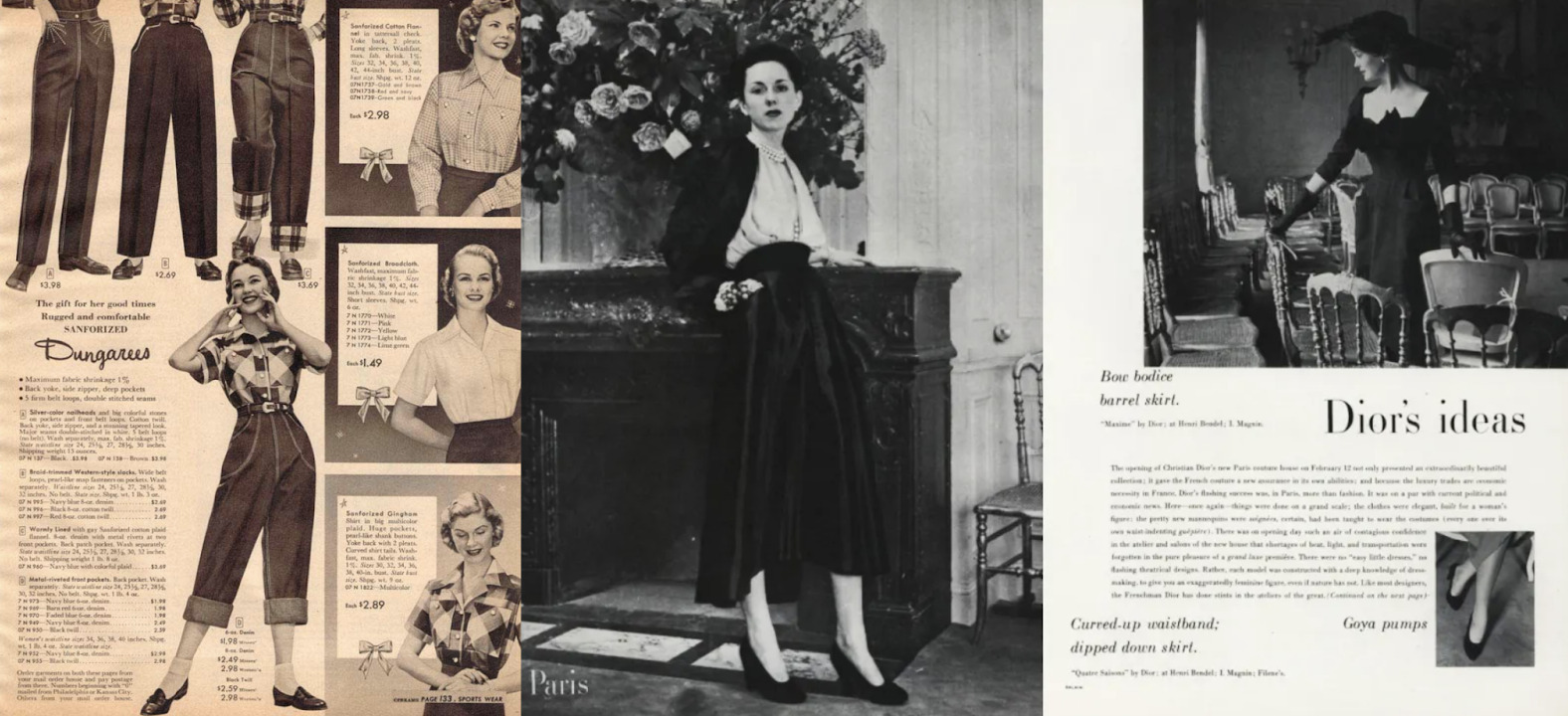

While there is no single inflexion point in history to indicate when hyperconsumerism took root, excess consumerism itself has been a steadily rising practice after WWII. Take, for example, Christain Dior’s revolutionary ‘New Look’ – the outfits were extravagant, directly countering the previous decade’s war shortages by using fabric as if it were cement in a sculpture. The new look did not promote the idea of buying things because they were basic needs. It promoted extravagance, a lifestyle centred around being fashionable – being in the know, something that persists even today. As time progressed, machinery made clothing more accessible, and fashion slowly rose out of the confines of private showrooms for deep-pocketed customers; There was something for everybody.

Credits: (Left) RetroWaste (Right) Vogue Archive

But why do we do this? Why is it an almost involuntary behaviour to reach for the latest clothes, the latest bag?

Earlier, we said that markets create demand – but why?

Take a look at India’s history. 70-odd years ago, the things we take for granted today, whether they are food, clothing, a room, or clean water were all luxuries. While there is still a prominent disparity in resource distribution, the situation has improved, and consumers are satisfied in the basic sense. However, conditioning by way of social mimicry or the bandwagon effect is what drives the modern fashion market. Humans naturally seek acceptance – they seek to be included, and if buying the latest shoes is the way, so be it!

Here is the final question – Is it hedonism, or conditioning?

Perhaps it is none, but in all likelihood, it is both. A mixture of unsatisfied existences and preying on that feeling to believe that consumerism is the answer.

Sweatshops and labour conditions

150 countries.

250+ million people.

Young, old, impoverished, left with no choice.

15 cents paid for what sells at 50 dollars.

And the list goes on.

The only way that micro trends and overconsumption caused by fast fashion can be met with cheap prices is through sweatshops with some of the worst working conditions in the world.

These companies desire to fill their stores with the latest trends as fast as possible hence making sure people involved in manufacturing are working in as little time as possible and charging just as less money. These materials and labourers are sourced from underdeveloped and poor countries.

Credits: DoSomething.org

The labourers cling to these jobs despite the inhuman conditions as it is their only source of livelihood. To reach the mainstream media or fight for their rights is a far-fetched idea for them. The supply chain for these sweatshops is so complex, ordinary middle-class people never realize they are using products involving slave labour and child labour. These people produce up to twenty shirts an hour while being paid as little as three cents a piece and these same shirts are marketed in fancy stores for more than thirty times the manufacturing cost. Employees in sweatshops are mostly women and children who work twelve hours a day only to earn the bare minimum in risky areas. The biggest retailers in the fashion industry often make it into the headlines for illegally outsourcing their clothes from sweatshops with dreadful working conditions, which risk thousands of lives in danger at just one location.

As soon as any of these brands are exposed, they pretend to care and market it to their audience, forcing factory inspectors to lie, making false claims, and ending their contracts in sweatshops, only to immediately look for another one.

Brands these days participate in greenwashing their clothes where they market their products to be sustainable but as high up to ninety-six per cent of these claims are usually false.

Yet, this shows their brand in a good light and leaves no harm to these vicious corporations.

Ethical Dilemmas Surrounding Fast Fashion

Have you come across the ideal dress that you have tried on previously and know it looks fabulous? Well, it’s currently on sale at a massive discount, almost being given away by the store. The question is whether you should buy it.

For some individuals, it’s a straightforward decision. However, it raises ethical issues for others whenever they shop for clothes. Which is more important, the way the item was produced or how much it costs? Is the essential information on the label or the price tag?

The fashion industry is infamous for profiting from worker exploitation, making it one of the world’s industries. This is partly due to the striking contrast between how fashion is produced and advertised.

There are now more individuals working in exploitative situations than ever before. The garment industry employs millions globally, with Asia alone accounting for 65 million garment sector workers.

Courtesy: BuzzFeed

Ethical consumerism involves political activism and operates on the belief that market purchasers consume the products themselves and the underlying processes used to create them. Consumers can embrace or reject ethical principles regarding labour and environmental practices. The drive towards ethical consumerism in the fashion industry can be seen in movements advocating for animal rights, fair wages for workers, and the use of sustainable materials.

Despite its good intentions, ethical consumerism has been criticised as a problematic commercialisation of ethics. Wealthy consumers may unfairly impose their ethical consumption practices on those who cannot afford ethically-produced items.

This presents a problem – fashion and capitalism are tightly intertwined. The rapid pace of fashion trends drives sales and the frequent turnover of low-cost, high-volume items on the high street, which are the primary goals of the fashion industry in a consumer-driven society.

Wearing clothes is a way to express oneself, and this self-expression can be considered a form of art. However, when the desire for wealth and power results in the oppression of vulnerable people and limits the freedom of expression, society must act swiftly to restore justice and address the exploitative practices of the industry that restrict individuality.

One can lead a relatively ethical lifestyle in a consumer-oriented society by controlling their buying habits, including both fast fashion and ethical brands. It is crucial to recognize the inherent worth of clothing and not merely consume and discard them without thought. All stakeholders, including producers, retailers, and consumers, have a crucial role in developing a sustainable fashion industry.

The toxic culture of hyperconsumerism in the fashion industry is where trends and collections are created to cater to the demand they create, perpetuating a vicious cycle of production and consumption that is harmful to the environment and society. Society needs to question our consumption patterns and think about the true purpose and necessity of their purchases, emphasizing the need for a more sustainable and conscious approach to fashion.

To address this issue, it is important to support sustainable fashion practices that prioritize fair wages, worker rights, and environmental sustainability.

Sustainable fashion refers to the production of clothing, accessories, and footwear that is environmentally and socially responsible. This means using materials and manufacturing methods that have a minimal impact on the planet and its resources, as well as treating workers fairly and paying them a living wage. Sustainable fashion also involves reducing waste and pollution and promoting circularity by designing products to be reused, recycled, or composted at the end of their life. In essence, sustainable fashion aims to create a more equitable and sustainable future for both people and the planet.

Despite all of this, sustainable fashion can be inaccessible for those who cannot afford higher prices, have limited availability in their area, lack awareness or education about sustainable fashion, or do not have access to size-inclusive options.

Sustainable fashion is still a niche market, and many sustainable brands may not have the same level of availability as fast fashion brands. This can make it difficult for consumers to find sustainable clothing in their local area or online.

Breaking out of the cycle of hyperconsumerism is not a one-step process but it starts with each one of us being just a little bit more conscious of our purchases and shopping habits.

Written by Rachana Raman, Vanshika Jain, and Jahanvi Singh for MTTN

Edited by Shivraj Herur for MTTN

Featured Image courtesy of Media India

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.