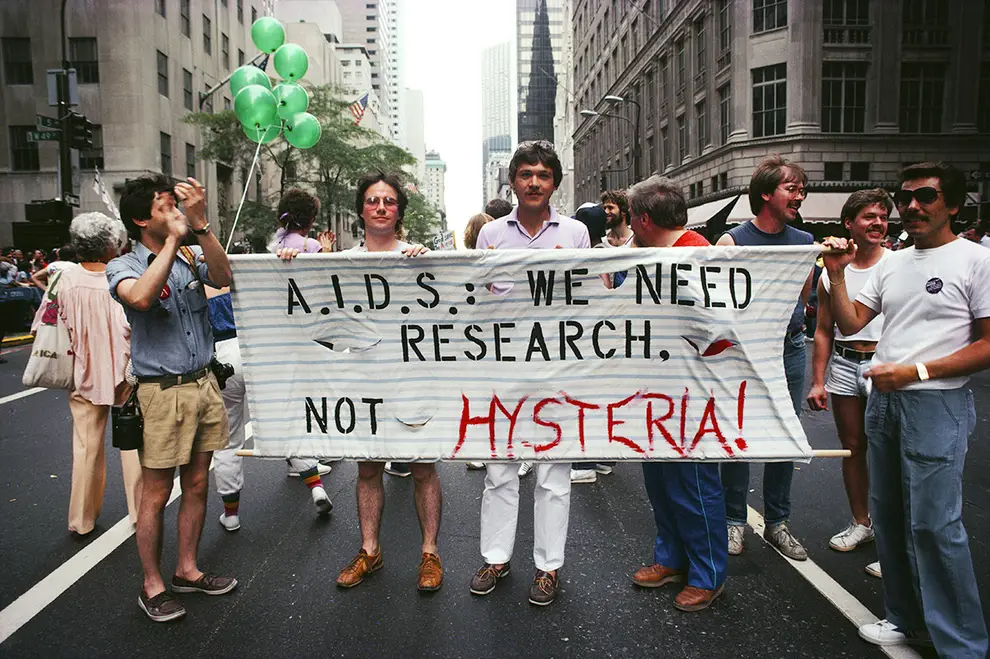

Black t-shirts with pink triangles. Cardboard gravestones with the words “Dead from Greed” written in dripping black.

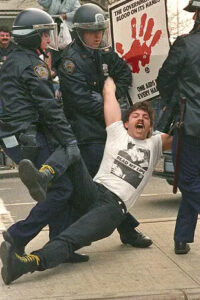

Ashes scattered on the prim grass of the White House lawn; Police horses trained to stomp over innocent protesters on suffocated streets stained with the crimson of the dead.

Wall Street turned into a war zone with angry yet hopeful HIV/AIDS activists fighting malicious pharmaceuticals and an even more insidious government that provided next to nothing for research.

Waves of smoldering anger rose among protesters across the globe to fight against a pandemic that threatened the delicacy of their democracies.

It was a disease that excavated our society and exposed the decaying bones of unjust marginalization and deep-rooted ostracization of a community of immunocompromised who were looking for ways to live, be it with AZT or a gallon of chlorine.

The first case of AIDS was reported in the summer of 1981 in the USA. It spread like wildfire, changing its name from GRID to the more scientifically apt HIV. But it reached the eastern coast of India in 1986, when a young Ph.D. student under Dr. Suniti Solomon, Dr. Sellapen Nirmala, screened migrant sex workers in Tamil Nadu for her dissertation.

The thought of such an impure disease invading the god-loving people of the state was outrageous.

But Dr. Nirmala took the chance and collected samples from remand houses with no gloves, stored them in her own refrigerator, and transported them to the nearest ELISA testing center, which was 200 kilometers away in CMC, Vellore.

Six out of 100 samples tested positive for HIV/AIDS, and things were never the same again. The deadly virus had infected a country that considered itself too virtuous to have it.

It was confirmed that the epidemic had spread its talons in the red corners of the country and was seeping into the kitchens of housewives with flowers in their hair and henna on their hands.

The total number of active cases in India currently stands at 2.4 million, while the ANI (annual new infections) stands at 63,000.

The numbers have scaled down from their peak in the 1990s, but doubts still cloud the efficacy with which drugs are distributed to the Indian public.

Yusuf Hamied, the chairman of the Indian pharmaceutical giant Cipla, stunned the world by providing a cocktail of antiretroviral drugs at $350 per year.

At the same time, their western counterparts leeched $17,000 per year out of their “target demographic.”

Sadly, there is still a deficit in the domestic distribution of these life-saving drugs because Indian companies export more than they provide to their own citizens.

In 1992, the Government of India launched the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP), intending to reduce infections while providing medical healthcare to patients.

Launched in five phases, each of which had positive implications for the dire condition of the disease, NACP has been regarded as a success story.

The National AIDS Control Organization, NACP, has been thriving and flourishing by providing affordable drugs and therapy to the prone populations of the country, mainly sex workers and migrant workers.

The efforts made by the governments of the world have helped us understand the mechanics of the disease and curb its crawling limbs from ravaging every cell of our body.

Increased media coverage of protests and riots enabled people surviving with AIDS to speak their truth about living in a crumbling body and a world that revered skewed trade laws over appropriately priced drug distribution.

We have come a long way since the obscure origins of the virus, which threatened to break the fabric of the world. Research has helped manufacture a drug that blocks transmission from a cheerful mother to her child, but we are far from perfecting the miracle drug that could end HIV/AIDS.

There is none in sight, but there is hope with efforts pouring in from scientists worldwide. Hope that its jagged synonymity with death softens and offers the survivors their sight and voice back.

Written by Vaishnavi Katiyar for MTTN

Edited by Aarthika Srinivasan for MTTN

Picture by Barbara Alper and Mark Peterson

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.